Happy in Spite of Every Thing....

Mansfield Park, Austen's neglected masterpiece....

Mansfield Park (MP from now on) I have always felt is one of the more interesting and overlooked of Jane Austen’s six novels, despite it being the least popular with her own family and many of her readership. Its heroine is a timid, frightened bullied child for much of the novel and its ending is darker than her others - the sole happy marriage overshadowed by the shattered ruined lives of the novel’s other characters.

Readers down the years have taken this as an indication of authorial weakness, that the novel is simply not as good as the others- that Austen took on more than she could cope with in it. But in my opinion this is a mistake. Although Austen’s novels are superficially similar all about courtship and marriage, under the hood of her plots she was always experimenting with the genre, and using it to explore a wide range of social and political issues.

I think that in MP in particular Austen pushed her topics and readership into much more mature and sophisticated territory - introducing controversial social themes like slavery, and forcing her readership to question their championing of characters based solely on their charm and wit. Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice is an easy heroine to root for - but Fanny Price in MP is a bullied child/woman in a hostile environment forced to make difficult moral judgements. Some of her readership in my view found this uncomfortable and projected that discomfort into a visceral dislike of the vulnerable heroine Fanny. This sometimes seems to go beyond mere disapproval and veers into the kind of bullying that Fanny’s Aunt Norris’s does to her in the novel. For instance the critic Claro Cavo said in 2002 that Fanny was:

‘priggish, passive, naive and hard to like’

Even Austen’s own mother said of Fanny that she was ‘insipid’. It is hard to believe that so skilful a novelist as Austen could not have anticipated these reactions - and I think she did. My evidence for this is the novel’s narrator’s protective remark about Fanny - the only time in her novels where she ever steps into the narrative to claim ownership of one of her characters -

My Fanny indeed at this time, I have the satisfaction of knowing, must have been happy in spite of every thing,

(It would be easy to identify this as Austen’s own voice speaking here - but since Austen invented the ‘unreliable narrator’ genre in ‘Emma’ this may be an unwise assumption).

Austen took the even bolder risk of presenting Fanny in direct contrast with a superficially attractive counterpart: Mary Crawford, whom many readers prefer and to whom they transfer their allegiance. To compound her readership’s discomfort she then takes them away from the comfort zone of an upper class house to the hard scrabble settings of the Price’s home in Portsmouth - full of dirt and disorder. I think Austen asutely anticipates that this may be another reason for some of her readers to project dislike onto Fanny who, by her refusal to marry Henry Crawford and defying her uncle, has transported them to this uncomfortable setting - putting them on the same side as Sir Thomas and Mrs Norris (to be clear I am suggesting that in MP Austen deliberately presented her readership with a scapegoat as described by Rene Giraud who then align themselves unconsciously with the bullying tendencies of the novel’s villains like Mrs Norris and the Bertram girls in order to flush out their unconscious prejudices - more perceptive readers might then be lead to critically examine these hidden beliefs ).

The Portsmouth scenes in MP also dig a bit deeper under the surface of the economic realities of Georgian England. All of Austen’s novels circle around money, or the lack of it. In P&P - she doesn’t sugarcoat the dilemma of being a woman in a world completely dependent on male provision, but Mr Bennet is a gentleman farmer, his money comes from the land around his comfortable house and he invites his future sons-in-law for a shooting party to show it off.

In contrast in MP Austen hints strongly that the big house and affluent lifestyle enjoyed by the Bertrams comes from a much more morally dubious source - the slave plantations of the Carribbean. The name of the house and the novel ‘Mansfield Park’ is I believe is a reference to Chief Justice Mansfield - whose judgement against slavery in 1772 was a key plank of the abolition movement (and since many of Austen’s relatives were abolitionists it make its very likely that she knew of the case). She makes reference to Sir Thomas going to his sugar plantations in Antigua (which used enslaved labour) and also that Fanny asks him directly about the slave trade; a brave question from a teenage girl to a powerful older man - which goes pointedly unanswered.

Austen lived in a time of great social turmoil - Georgian England was a time of state paranoia around imminent Napolenic invasion. It was also in the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Irish 1798 rebellion which caused much anxiety in the English elites that the same thing might happen there. The armed militia which appears in P&P in the nearby town of Meryton - which for the Bennet girls was only a source of exciting new opportunities for socialising - although ostensibly there for protection from foreign adversaries like Napoleon - was in reality intended as visible shows of strength by the authorities to maintain public order.

That threat was not just a figment of official imagination - although barely hinted at in Austen’s novels where physical violence rarely features - the downstream effects of the enclosure of the commons by landowners resulted in large amounts of poorer rural inhabitants in the early nineteenth century being pushed off the land and into the cities and this caused regular countrywide food riots. The official response to this was often gratuitous violence like the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester. Another response and as a visible deterrence, various militia were formed and stationed in large ‘man camps’ dotted around the country which were in themselves also a potential source of drunkness, disorder and violence in the communities they were situated (Mr Bennet might not have been alone in breathing a sigh of relief when the militia left Meryton).

But the risk of being on the receiving end of violence from marauding soldiers, or falling foul of the draconian Georgian penal system where even minor crimes were punished by execution or transportation was not the only way that Georgian England exerted power over its citizens. Even those further up the social scale who challenged the existing power structures left themselves open to severe reputational damage. Women were uniquely vulnerable to this type of attack - for example Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire involved herself in political campaigning for the Whig party and thus made herself a target for outrageous sexual innuendoes and smear campaigns from the popular and gutter press (what might be regarded today as a ‘monstering’).

Austen, as a single woman from the lower middle classes without a private income was particularly vulnerable in this society and therefore had to be very cautious. She retained her privacy as long as she could, publishing anonymously as ‘A Lady’ or ‘The Author’ in several of her novels - in an attempt to deflect criticism. But Austen also had to contend with another more intimate threat - she was wholly dependent on her male relatives for support. This circumscribed what she could and could not write about - if she strayed too far outside the confines of what her male relatives approved of - by for instance, a direct critique of the slave trade then it is likely that she would have put under pressure by them not to publish (that she was even allowed to do so at all was remarkable in the circumstances).

There is a tiny sad vignette from her biography by Claire Tomalin when Austen was staying at her rich brother Edward’s mansion house in Kent and she asked him to arrange travel for her to a friend’s house because as a woman she couldn’t travel alone. This was only begrudgingly given when she had to reveal some ‘particular private reasons’ to him for her journey. In other words her brother (a rich man who had leaned heavily on his sister for childcare over the years) made her grovel to him as his price for minor help to her. This might go some way to explaining Austen’s focus on money in the novels, she knew what the lack of it meant and the price it could extract in personal dignity. But there is no evidence that she ever voiced this resentment to Edward directly - she couldn’t, because the power imbalance between them was so great (and her sister Cassandra made sure to destroy any indiscreet letters after her death).

This in my view directly informs Austen’s writing - powerful patriarchs like Sir Thomas in MP are very carefully drawn, mixing praise and cautious criticism, tip toeing around their flaws in ways that Austen herself must have done around men like her brother in real life. She does not say directly that Sir Thomas is an emotionally cold man whose income comes from human trafficking, but between the lines she does hint at it very strongly (and perhaps some of the function of the novels for Austen herself was to be a safety valve for this psychic tension, where Austen could subtly point out the flaws of the powerful men around her without being caught).

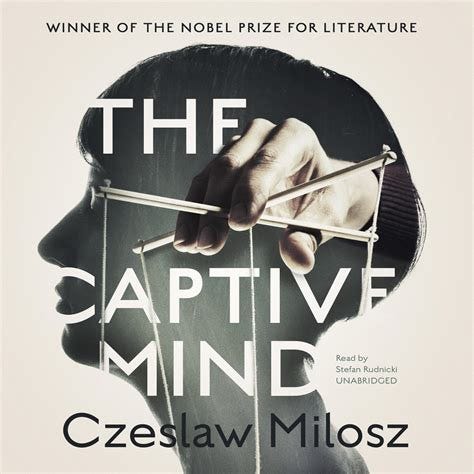

There is a modern precedent for this kind of double think - and it is brillantly described in the book by the Czech author ‘The Captive Mind’, this describes the experiences of those in the Communist countries of Eastern Europe after the Second World War where Soviet imposed ideological systems were internalised by constant repetition, education and state propaganda. Those who disagreed with the official line were forced by the all pervasive propaganda and constant state surveillance to adopt a kind of cognitive dissonance, saying one thing in public whilst believing something different in private. This he refers to as the practice of ‘ketman’ and he describes the cognitive juggling it requires, the retreat of the private self into limited settings amongst trusted companions (the more limited these opportunities become, the greater the pressure on the individual psyche - and Fanny’s lowest point in MP comes when her only trusted friend Edmund appears to desert her)

This is of course also a form of acting and it touches on the danger that Austen presents in the play ‘Lover’s Vows’ in MP - acting is a form of pretence which carries the danger of tipping into reality - words spoken in pretence can turn into genuine feelings. This is also a constant risk in highly authorian societies where constant repetition of the party line can become an integral part of an individual’s character, leaving those who disagree often left with a type of cognitive dissonance where they must hold two contradictory beliefs at the same time - a public and a private persona. Although this is a form of survival strategy, it can come at high personal cost as the constant cognitive juggling it requires can sometimes result in depression - something Austen herself is believed to have suffered from.

Austen in my opinion showed in her writing as well some indications of this ketman- juggling differing points of views in the ways that she draws male characters like Sir Thomas in MP. On the one hand, he is presented sympathetically as someone who has rescued Fanny from a life of immiseration and given her a comfortable home, and in the main, treats her with respect. But on the other the home he offers is paid for by the work of enslaved human beings thousands of miles away, so Fanny’s comfort is ultimately drawn from their misery - and she knows it.

But Fanny cannot afford to think or question this too much, as to do so is to threaten her own security. Her question to Sir Thomas about slavery is unanswered, because unanswerable, if Sir Thomas acknowledges that what he is doing is immoral on his slave plantations then the whole edifice upon which the economic security of the household depends crumbles. He could choose to disinvest himself of his West Indian properties and found a more ethical way of making a living - but he does not (Sir Thomas’s anxiety to have his daughter and niece marry rich men with landed estates might reflect his desire to launder his family name with more respectable sources of wealth and it might also explain his wish to have his younger son join the clergy).

The undertow in MP is of anxiety and the constant threat that Fanny feels herself under (and her enforced exile to Portsmouth shows that this threat is real). This indicates to me that Austen may have used MP to communicate at least some of the psychic reality of being a lower middle class woman in Georgian England, economically comfortable, but also vulnerable, liable to have the rug pulled from under you at any time, forced to keep silent or tell ‘polite lies’ in order to placate those on whom you both depended economically and for physical protection and security - those like her brother, whom you might fear, but also love at the same time.

I also believe Austen knew she was taking a risk doing this, that she wouldn’t take all of her readership with her on this journey and that her heroine would bear the brunt of their displeasure; but that she did so anyway. Perhaps she believed at least some of them would understand that the novel was a coded protest against powerful men like Sir Thomas (and maybe even her brother) using their economic and social leverage to bend vulnerable family members to their will.

But this ultimately fails in MP as most of Sir Thomas’s ambitions for his family are dashed, his marriage is an empty cipher, his oldest son is a failure, his daughters do not marry the rich men that he hopes they will, he does not succeed in forcing his adopted niece to marry the rich man he thought suitable for her. The only person who succeeds in his family is Edmund, the son who does not follow in his footsteps and becomes a clergyman. The niece he took in as a pity project turns out to be the one person who may provide the ultimate salvation for the family through a happy marriage to his son - although this is in direct contradiction to his wishes at the start of the novel when he worries that this might happend. By the end of the novel, this too is reversed - he now welcomes the alliance he previously feared and he has grown in self knowledge, realising that imposing his will on others does not produce happiness, even for himself (it’s an interesting parallel to his role as a slave owner).

But in the end it is Fanny’s wishes that have triumphed over his, by refusing the path that he chose for her to marry a man she didn’t love. This - like her planitive question about slavery to Sir Thomas took courage - courage Austen herself had - courage to risk disappointing and losing her readership in order to write her truth about women’s lives and women’s choices in a society run by powerful men who controlled the public narratives, who decided what could and could not be said and by whom.

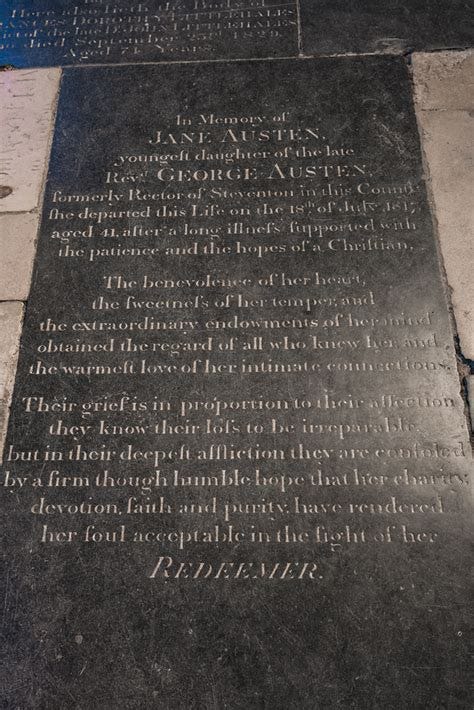

This also meant having the last word and men like her brother Henry took this literally - where after her early death, he composed her epitaph for her gravestone in Winchester Cathedral - on which there is not one mention of her writing, but instead lists all the ways he thought she conformed to the societal expectations of women of the time - her ‘charity, devotion, faith and purity’. But this final patriarchial power play failed - today we remember her for those unmentioned wonderful books. I like to think that would have pleased her and that - like Fanny - it would have made her ‘happy in spite of every thing’.

If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please hit the Like button at the bottom. And leave a comment if you’d like to share why.