Symbols give us our identity, our self image, our way of explaining ourselves to ourselves and to others. Symbols in turn determine the kinds of stories we tell, and the stories we tell determine the kind of history we make and remake. - Mary Robinson, Presidential Inaugural Address, 1990

Hail Mary…

Is Ireland now a post Christian society?

Recently I have been listening to a discussion here by the writer Paul Kingsnorth and the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams about whether much of the modern world has become a post Christian society (and whether they think this might be about to change) - and it chimed with my view (which I explored in a previous essay here ) that Ireland is no exception to this trend.

But what does that mean in practice?

Where are the Irish drawing our ideas of how we should live a good life from today?

And how is this reflected in our visual landscape?

If you take a drive down Irish country roads, it is common to pass small roadside grottos, typically with a statue of the Virgin Mary. In contrast, walking around Belfast, the streetscapes are bedecked with murals and flags indicating Republican or Loyalist sympathies. However increasingly in my view, many modern cosmopolitan Irish (and since the island is now 62% urban based, this is now the majority) view these visual traces of religious or political beliefs with eye rolling exasperation as gauche reminders of When We Were Superstitious But We’re Over It Now.

I’m Leaving On a Jetplane….

Today, instead of religious or political markers, the visual landscape of the island both North and South is increasingly covered with the trappings of modern consumer culture - for example in the multiple advertising hoardings around its cities and roadsides, but also in the visual branding of many big companies.

For example, you may not like the pugnacious CEO of Ryanair Michael O’Leary- but it is undeniable that, thanks to him, the distinctive blue and yellow livery of the budget airline Ryanair is now firmly linked in Irish psyche with cheap flights. However just as the iconography of religious or political artefacts in the past was freighted with a whole host of emotional and intellectual responses - like devotional reverence at a roadside grotto - or fear (try walking down a Belfast street lined with Union Jacks as a Catholic ) - these new corporate visual artefacts elicit their own emotional responses from their audiences.

One of mine is, as a frequent flier on O’Leary’s blue-and-yellow Sky Bus, is the suppressed irritation of being treated as part of a human herd to be shepherded through airports and on and off planes (and yet I still do it because Ryanair flies to places that I cannot otherwise get to). But each time I board one of his planes, I cannot help feeling that another tiny flake of my soul has been chipped off by Michael O’Leary.

It isn’t entirely O’Leary’s fault of course, airports in my view are Ground Zero of corporate branding - most of my experience of them is that they are interchangeable Global Anywheres where passengers are funnelled between heavily curated visual and physical spaces. Endless greedy panopticons of Starbucks or McDonalds eagerly monetise each passing glance alongside the relentless tailoring of every step of the passenger journey through the physical space of gates or corridors to suit the needs of corporate franchises, the State or airlines. Or to put it another way, I am sick of trudging through these overstimulating garish hamster wheels. Too much time in airports in my case leads to a kind of moral weariness - and I suspect that I am not alone.

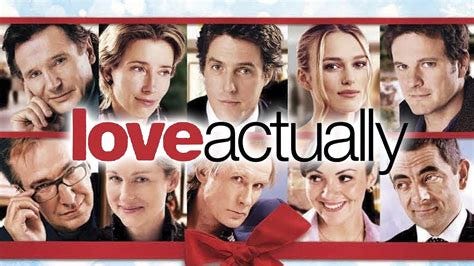

The 2003 Richard Curtis film Love Actually contained many airport scenes which to me obliquely address this underlying discontent that many others have in these places- and perhaps that was part of its success. Even - it seemed to say, in the most soul shrivelling environment like an airport - it’s okay because love is actually all around!

Love Actually….

General opinion's starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed, but I don't see that. It seems to me that love is everywhere….If you look for it, I've got a sneaky feeling you'll find that love actually is all around (Hugh Grant’s character as the British Prime Minister in Love Actually, 2003).

The film’s take home message seems to be that - despite your unease at being endlessly surveilled and policed in places like airports - it’s all fine, no real damage is being done to your soul or human relationships (conveniently ignoring the fact that airports are places designed around corporate or state interests and designed to minimise spontaneous human interactions) but it touches on a wider point which I call ‘sentimental humanism’ - which I believe is a increasing but dysfunctional response to rapacious capitalism and state surveillance and which I’d like to look at through the lens of Love Actually.

Although Love Actually is situated around Christmas, the intertwined stories in the film riff on the theme of love in its many guises without ever touching on religious or moral beliefs. This echoes many of my recent experiences speaking to Irish people of my acquaintance who argue that there is now no need to invoke beliefs in God or gods or anything outside of human constructs like kindness, equality, justice and environmental beliefs to scaffold discussions of personal, social or political issues.

The input of clergy in these debates are often now unwelcome - the recent discrediting of the Catholic Church has had much to do with this. The argument often goes that we are grown up adults (what is left unspoken is that this is usually means only safely middle class and educated of us) - and these are simply matters of opinion: not of conviction.

The confidence underpinning these assumptions is that - as the subtle messaging of Love Actually implies - most people are basically kind and decent and therefore no longer need full time moral guardians like clergy nor to be told what is and isn’t acceptable behaviour - so religion is redundant. And as the film Love Actually reassures us, love is all around us - human relationships are still flourishing.

This conveniently shifts our attention away from the role of corporate or state bodies in the design and control of our public spaces like airports - and the ways in which these environments actively undermine the wellbeing of individuals or discourage the opportunities for interpersonal relationships (the mean spirited sign at the top of the essay being a prime example). But films like Love Actually downplay this - it says that if if we can’t see love in these places, it’s our failure of imagination that’s to blame - not the fault of the corporate or state interests who have designed these places around their priorities and where human needs get squeezed out.

The Future’s Bright, the Future’s Orange….

The sentimentality of Love Actually is in my opinion the first time that an overly rationistic culture has provoked a sentimental backlash - this also happened in the aftermath of the Enlightenment, pioneered by the eighteenth century French writer Jean Jacques Rosseau followed by the later Romantic movement with the poetry of William Wordsworth and Shelley. Jane Austen asutely critiqued this trend in her novel ‘Sense and Sensibility’ in the character of Marianne Dashwood (to whom the lyrics of ‘Love is All Around’ might have been directly addressed).

This Georgian sensibility later curdled in the Victorian age into overt sentimentality - the aesthetics of this were cozy pictures of rosy cheeked children in middle class settings, the chocolate box images providing a warm bath of emotional comfort (the modern equivalent of this might be bumper stickers with platitudes like ‘Be Kind’ or the internet memes of animals or children). But this faux reassurance of Victorian sentimentality where pretty pictures were painted of middle class children but poor ones were sent up chimneys was called out memorably by Charles Dickens in his novels like Bleak House or Oliver Twist.

Sentimental humanism re emerged in various guises in popular culture over the next century, from the frankly terrifying Nazi German cult of Kinder, Kuche, Kirche in the 1930s to the faux domesticity of 1950s Doris Day films like Move Over Darling.

But in Ireland, which was until fairly recently a largely religious society - much of our visual aesthetics leaned, not into the tropes of sentimental humanism, but instead heavily into the visual trappings of Catholicism like Sacred Heart pictures or statutes of saints - or in Northern Ireland into the trappings of political ideologies like Republicianism or Unionism. In 1996 there was a clumsy clash in Northern Ireland between these traditional aesthetics and corporate messaging when the UK mobile phone company Orange had to drop its strapline of ‘The Future’s Bright, the Future’s Orange’ when they belatedely realised that, umm, this message wasn’t quite landing the way they expected (Orange being a synonym for the Loyalist community).

But since many of us have ditched the rosary beads and saints - there is now another secular source of visual symbolism that is being increasingly leaned into - our Celtic mythology full of stories of beautiful young women with delectable swirling dresses, fabulous jewellery and what seem remarkably like a modern high school football team - Fionn McCool and his bunch of spears-for-hire, the Fianna. As a bonus pre-Christian Celtic mythology also includes a Marvel type action hero - Cu Chlainn- a man of superhuman strength who fights entire armies off all by himself. The aesthetics of this are captured nicely in the highly stylized art of Jim Fitzpatrick - and conveniently it all lends itself very well to marketing everything from chocolates to whisky - What’s Not To Like?

Dublin Airport certainly agrees - here there is a wall of murals of the Greatest Hits of Irish mythology to gently steer incoming passengers that they are lucky to land, not in Global Anywhere, but in a land of poets and mystic landscapes (an impression that will be rudely dispelled as soon as they set foot in Dublin city centre). The fairy dust of Celtic symbolism is also lightly sprinkled over the jewellery, chocolates and whiskies in the Duty Free Shop.

The vibe around all of this seems to be is that Ireland is returning to its roots - before those Christian buzz killers turned up - to a society where the Fianna roamed the countryside like bands of grown up Boyscouts, in the absence of oppressors like the English (boo!) - at one with nature, creating beautiful music and poetry and occasionally having regretable- but totally understandable - fallings out over stuff like girlfriends or - umm, giant bulls - and where the men were Bear Grylls wilderness types but whose women were feisty girl bosses like Queen Maeve (the Irish Boudicca) In fact, all a bit like modern Ireland in fact - minus the cattle and spears - and with better hair and jewellery.

Unfortunately might be a case of using pre-Christian Ireland as a dressing up box for today’s sensibilites. There is for example some genetic evidence that up to two to three million men of Irish descent alive today descend from just one fourth century Irishman, known in legends as Niall-of-the-Nine Hostages. If this is the case it would appear that this might be the Irish version of Genghis Khan - another male who fathered multiple children and wasn’t exactly known for his peace ’n’ love vibe (there’s also a bit of a give away in the ‘hostages’ moniker).

Did That Play Of Mine Send Out?

If we are leaning more into our pre Christian past - this wouldn’t the first time this happened, nor that it has been used as a mirror for more modern sensibilities. At the turn of the twentieth century the Irish Celtic revival saw people like Cesca Trench, a vicar’s daughter from Surrey, move to Dublin change her name to Sadhbh Trinseach and sport a self designed Irish national costume around Dublin (the writer James Joyce subtly mocked this fashion in his story ‘A Mother’ in The Dubliners).

The uber poster girl for the Celtic Revival must be the poet W.B. Yeats’ muse Maud Gonne - the middle class English girl from Hampshire who turned herself into the personification of Ireland in his play Kathleen Ni Houlihan. The play centred around a mythic view of Ireland as an old woman calling on a young man on the eve of his wedding to take up arms to defend her and was a coded protest against British rule. But all this LARPing of mythic Ireland turned very dark on Easter Monday 1916 when a staging of the play was cancelled as some of the cast of the play took to the streets rebelling against British Rule and one of them - Sean Connolly - was shot dead while mounting an attack on Dublin Castle.

This was all came as a nasty shock to Yeats (it was just a play, duh!) and many years later in his 1938 poem ‘The Man and His Echo’ he asked himself in anguished question:

Did that play of mine send out? Certain men the English shot?

(Short answer William, yes….)

‘Mé a rug Cú Chulainn cróga’. (translated I who bore Cu Chulainn) from ‘Mise Eire’ poem 1912 by Padraig Pearse

One of the leaders of the Easter 1916 Rising was the poet Padraig Pearse who had also mined the Celtic past for symbolism such as the mythic hero Cu Chulainn to evoke a new kind of Irishness. However what Pearse didn’t reckon on, or indeed ever see, as he was executed immediately after the Rising - was that his choice of Cu Chulainn was more presicent and ambigious than he could ever have imagined. At the end of the mythic story the Cattle Raid of Cooley Cu Chulain having previously been forced to kill his best friend Ferdia in single combat, fell in battle at the hands of his fellow countrymen. This has tragic echoes of what happened after the 1922 Anglo-Irish Treaty ending the Irish War of Independence when former comrades turned on each other in the Irish Civil War and the new Irish Free State executed more of their fellow countrymen than the British had done in the preceding years.

They are the Advertisers and they are laughing at you….(Banksy, 2012)

So in short what has traditional Irish iconography; the visual tropes of corporate branding like Ryanair; or the sentimental humanism as portrayed in Love Actually have to do with each other?

In my view there are several conclusions to be drawn:

The dangers of carpeting our visual landscape with manipulative corporate messaging were powerfully pointed out in 2012 by the street artist Banksy. Since I cannot better his words, I strongly recommend you read his diatribe against The Advertisers here. Suffice to say that I completely agree with him that surrounding ourselves with a polluted visual landscape is not likely to make us happy and that is its point.

That sentimental humanism as portrayed in Love Actually is not the answer to our failure to counter these attacks of rapacious capitalism on our sensibilities, our distress is real, and justified. It is, in my view, a form of gaslighting to imply that the discontent we experience from our visual and built environments has no effect on our well being or relationships. People do still of course embrace at airports, but these spaces are entirely controlled by corporate or state interests and their needs dominate their design, there is little or no effort made to accommodate human needs or relationships. What is all around us there is not love, but relentless advertising and corporate and State manipulation; love is still there despite this.

Sentimental humanism can also valorise emotional comfort over difficult ethical or moral choices - it conflates feeling good with being good (the scene in Love Actually where the boy runs through airport security to tell his school crush how he feels about her is a prime example of this - we are invited to cheer him on when in practice most of us would immediately stop him).

There are other drawbacks to the sentimental humanism as portrayed in Love Actually, for instance: it is one which only contains the views of those comfortable enough not to worry about basic needs like food or shelter and it can be a myopic shelter for idealism untethered to reality - but that is outside the scope of this essay.

In summary I believe:

That if we do not wish to find ourselves power hosed away by the out of control consumption and greed fostered by rapacious capitalism shielded by sentimental humanism which is wrecking our country and our culture it may be time for all of us in Ireland to reinvent a collective national mythology and symbolism based on shared values.

That in my opinion at least some of the ancient Irish myths are powerful intergenerational sources of symbol and story which might yet prove useful in this endeavour (but to also realise that these myths are potent and potentially dangerous cultural weapons and should not be carelessly invoked or monetised).

But perhaps if we do so with care there is a chance that, in the words of the modern Irish scholar Ciara Ní Bhroin:

For a nation that, in recent decades and at great cost, has privileged the individual over the community and the economy over society, mythology may be inspiration for a regenerative collective vision – neither a nostalgic harkening back to the past nor a synthetic packaging of the past for commercial gain, but a transformative, self-renewing narrative to sustain upcoming generations into the future.’

Amen to that….

I haven’t flown in the last eight years so it was quite the surprise to see that hug restriction.

Does the airport think that weapons or secret messages could be transmitted? If so, they’re more gullible than a dog chasing a stick that its owner only pretended to throw. Both can be done in seconds.

Does it think passengers will become so wrapped up (pun intended) in their hugging that they’ll miss their flight?

Or do they frown on a three minute five as the potential loss of revenue at an overpriced ‘restaurant’?

I remember once arriving at my destination late in the evening with the luggage crew likely on break - around 11 PM. This was somewhere in the US some time ago. When the luggage finally came down the carousel it was already after midnight. Everyone grumbled and grabbed, whisked away in their cars or in those waiting for them.

I had already missed my connecting flight and, stranded for the night (this was before smartphones), then wandered about. Everything was closed. I finally found a janitor who pointed out the security staff office. They told me there wasn’t anything they could do but I was welcome to sleep on the cold floor.

My love of flying has never been the same since then,