This is a deep dive into Irish history and how culture was used in it to promote political causes. I’ve put it in chunks, the earlier sections are for those unfamiliar with Irish history, feel free to skip those if you like, the real meat is at the end. All images and clips are on a ‘Fair Use’ basis, as this is a non profit blog. (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/exceptions-to-copyright)

My late father’s favorite party piece was the Irish song ‘The West’s Awake which he sang with verve and gusto belting out lines like1:

And fleet as deer the Normans ran, Through Curley’s pass and Ardrahan.

This could sometimes be a little awkward for me when visiting home with English friends, not because of the anti English sentiment in lines like :

Sing oh hurrah, let England quake!

as they knew by experience that this bore no resemblance to how he, or indeed most Irish people, felt about any actual living English person, but instead by the whole premise of the song, that there was an entity as ‘the West’, (a collective description of the thinly populated counties of the Western seaboard of Ireland - in American terms it would be like saying ‘The West Coast is Upset’, it doesn’t make sense). And the idea that the recitation of long ago battles in tiny Irish towns, and the implicit threat in the song’s title, might have any current relevance or resonance today is also something that baffled them. Why, they might well ask, should we care if the West is asleep or awake?

This is on the face of it an entirely reasonable point of view as there has never been to my knowledge a time where all the people collectively in Galway, Sligo or Roscommon and the rest of the counties of the Irish Western seaboard got out of bed one morning and decided that henceforth they are going to Take No More Nonsense from London/Dublin/Brussels/Washington. It’s also a fairly safe bet that no one in these powerhouses of the globe, or indeed ever in world history, has paused for a millisecond and thought, ‘Hang on, how is this going to play in Ballinasloe/Ballina?’

To meme or not to meme…

In short the threat in the song has shades of the famous headline from the tiny Kerry newspaper the Skibbereen & West Carbery Eagle which thundered in its 1898 editorial that:

[The Eagle] will still keep its eye on the Emperor of Russia and all such despotic enemies — whether at home or abroad — of human progression and man’s natural rights which undoubtedly include a nation’s right to self-government. 2

which has become a touchstone in journalism for either taking yourself way too seriously, or a mischievous dig at the self importance of journalists, depending on whether you believe its writer, the Welsh Protestant Fred Potter was just plain delusional, or a tongue-in-cheek provocateur mischievously looking to boost his paper’s subscribers against recent competition (and they do have form for that in this corner of the world)3. Despite the entirely predictable mockery from Dublin and London at the time and since, nearly a hundred and thirty years later the people of Skibbereen are still proudly using the ‘Skibbereen Eagle’ to sell everything from whiskys to pubs.4

The ‘Eagle is keeping its eye on the Tsar of Russia’ is an example of a meme, a type of mind virus which I have written on here and as described by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book ‘The Selfish Gene’: 5

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

The power of these memes or ‘mind viruses’ were well understood in early Irish culture and the creators and guardians of them, the professional Irish poets, the fili, were well known (and feared) for their cultural power (again I have written about this here). There were good reasons for this - culture could be weaponised- quite literally in some cases, for example the sluaghghairm (from where the modern word ‘slogan’ comes’) was the war cry of an Irish clan in battle, for instance that of the O’Neill clan of Ulster was ‘Lámh Dhearg, Abu’, (the direct translation of this is ‘Red Hand, Win!’ which tracks to the Red Hand presently seen on the Northern Irish flag). The efficacy of these was recognised by the proclamation by the King Henry the Eighth:

Wherefore we straightly charge and command all our loving subjects, as they tender our pleasure and will not incur our high displeasure, that from henceforth they or any of them do not use or speak any such words as ‘Crom-abo, Butler-abo,’ or other words like, in their wars or fights, but to call only on St. George, or the name of his Sovereign Lord the King of England.”

Act of Parliament, Henry VIII, 1537

As well as their war cry, the clan’s group identity also depended on a descent from a common ancestor, a shared history and often links to particular landscape features. Prior to Cromwellian invasion the main allegiance of most native Irish was to their individual clans in their local areas, an island wide consciousness- a distinct sense of ‘Irishness’- was vague at best amongst the general population6.

The grey wing on every tide…7

The Irish Cromwellian land confiscations in the seventeenth century, which I wrote about here, not only transferred the physical ownership of vast swathes of land across the island of Ireland, it also destroyed the clan system as large numbers of people were dispersed from their ancestral lands and their traditional allegiances. The Williamite wars of late seventeenth century, in particular the dispersal of the Irish soldiers to the Continent in the so-called ‘Flight of the Wild Geese’, completed the process as these included many of the traditional clan leaders and their families, and funnelled further power into the hands of the Anglo Irish elites and the British State.

However, attempts by the British State to further cement their control over native consciousness by promoting the Anglican Church on the island met with stiff resistance as most Irish refused to shift their spiritual allegiances away from the Catholic Church. The State sought to undermine this in part by discriminatory practices such as barring Catholics from political office or from certain professions like the law and certain army ranks.

In all their loneliness and pain..8

But by the beginning of the nineteenth century Ireland was in a pretty sorry state, the Act of Union which abolished the Irish parliament in 1801 had reduced the island to a vassal state, eviscerating native industries and the Anglo Irish political classes had largely migrated to London, leaving the country with a sizable disgruntled Catholic middle class shut out of most government jobs. Large portions of the island’s land mass had been devoted to the growing of cash crops like wheat, oats and barley to support the Napolenic war efforts, thus rendering the native peasantry ever more dependant on a single crop: the potato for sustenance.

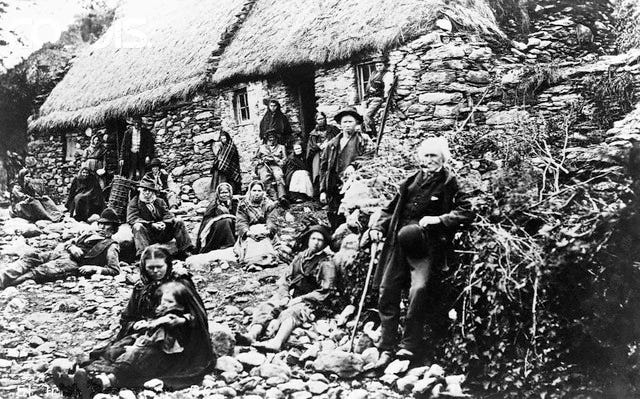

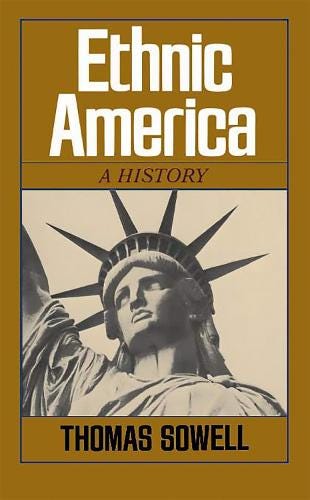

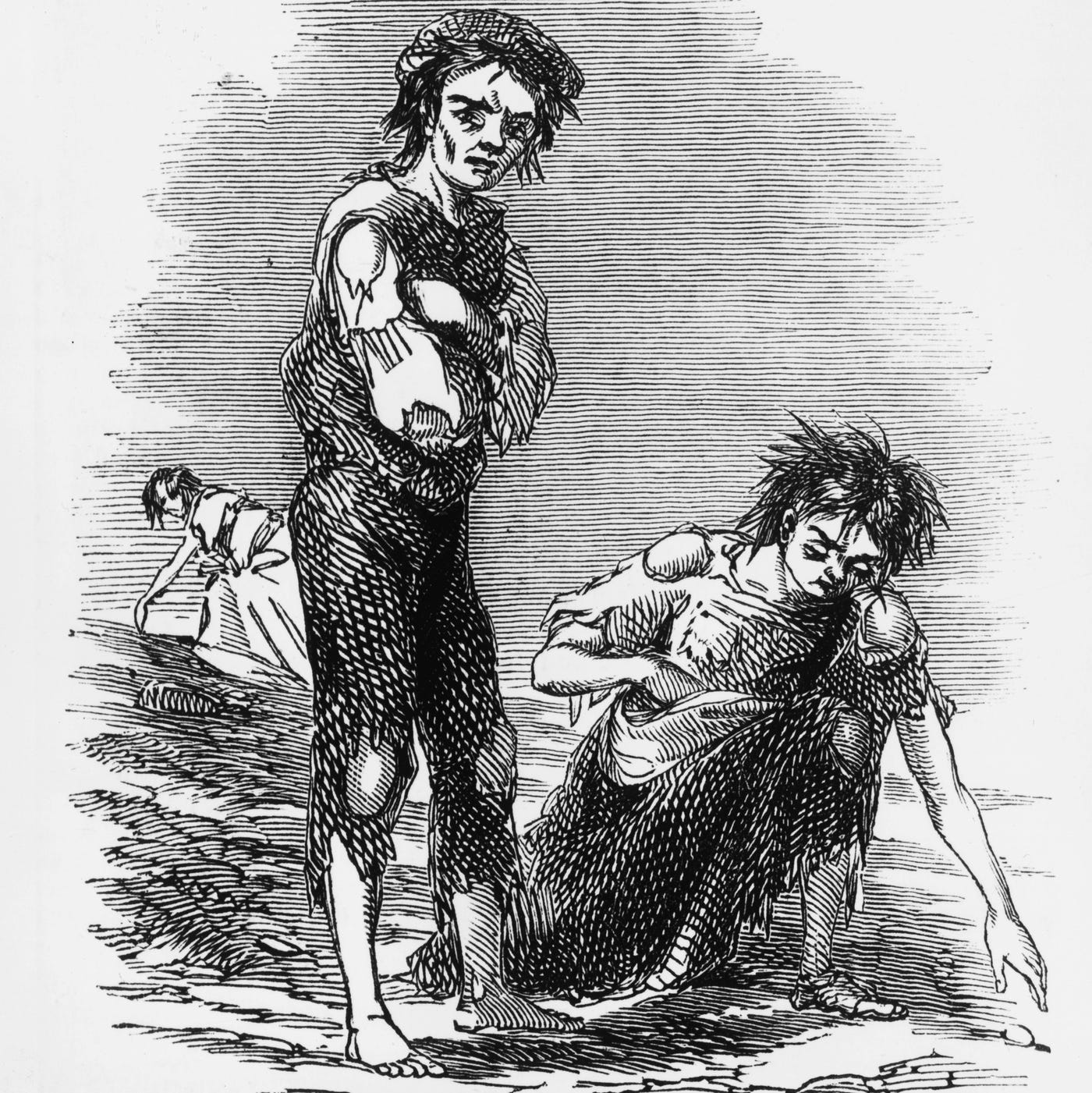

But the end of the Napolenic wars in 1815 lead to an economic crisis on the island with a steep fall in the prices of cash crops like barley and wheat and the near collapse of the Irish banking sector9. This was followed by a series of mini famines caused by periodic failures of the potato crop and it meant that a number of foreign visitors to the island wrote searing indictments on the dire poverty and sheer wretchness of the majority of the population10. Thomas Sowell, the eminent sociologist wrote in his 1981 book ‘Ethnic America’:

Slaves in the United States had a longer life expectancy than peasants in Ireland, ate better, and lived in cabins built of sturdier materials, with more space, ventilation, and privacy, than the huts of contemporary Irish peasants. It is unnecessary to attempt to say who was worse off on net balance. The mere fact that such a comparison could be made indicates something of the desperate poverty of Irish peasants in the 1830s11

Around this time there was a sharp rise in agarian violence, with local militia groups like the Whiteboys and Peep O’Day boys expressing the peasantry’s discontent with the straitened circumstances they found themselves in. (The British government stung by the repeated criticism and alarmed by the rising violence in Ireland did what it usually does in response to any crisis, from the Post Office to Grenfell - it set up a Commission to investigate it- the Devon Commission in 1843).12

The Greatest Popular Leader…

It was from this background that the arrival of the legendary Irish politician Daniel O’ Connell and his campaign for Catholic Emancipation, the removal of restrictions on the rights of Catholics to become members of parliament and other bars, onto the political scene was to prove so transformative (he was also a staunch anti slavery advocate). O’Connell, known in Ireland as ‘the Liberator’ and whose statute stands in the main street in Dublin named after him, was an advocate and pioneer of non-violent methods of political resistance (he had inadvertently killed a man in a duel as a young man and thus sworn off violence for life). He was perhaps the first truly modern political figure in European history. Even his English opponent the British Prime Minister William Gladstone wrote of him in 1889 saying:

Almost from the opening of my parliamentary life, I felt that he was the greatest popular leader whom the world had ever seen13

An inspiring speaker, he was one of the first politicians to harness the power of the press to reach the newly literate masses as well as using as well as harnessing the power of history and myth to bolster his popularity, he staged ‘monster rallies’ bringing many hundreds of thousands of people together at emotive locations in Irish history such as the Hill of Tara, or the former battlefield of Clontarf. O’Connell also yoked Catholicism and nationalism together saying:

the distinction created by religion…was the positive and unmistakable mark of separating the Irish from the English 14

although many of his allies in the Repeal movement were Protestant, O’Connell saw that the power of the Catholic Church over their congregations could be leveraged for political ends. This early harnessing of spiritual power towards political ends had unfortunate downstream consequences later in the nineteenth century, and the centuries which followed, but O’Connell’s Christian nationalism’s influence can still be seen today in current US politics. O’Connell, although a fluent Irish speaker himself, spoke only in English at his rallies and was completely indifferent to the Irish language saying:

I am sufficiently utilitarian not to regret [the] gradual abandonment [of Irish]... Although the language is associated with many recollections that twine round the hearts of Irishmen, yet the superior utility of the English tongue, as the medium of all modern communication is so great, that I can witness, without a sigh, the gradual disuse of Irish.15

But he was not blind to the political uses of other aspects of Irish culture, using Irish music, often the famous songs of Thomas Moore, like ‘The Harp That Once16’ at his ‘monster rallies’ to good effect.

Several young intellectuals in O’Connell’s vanguard, although they shared his aim of Irish independence, did not agree with his assessment of the Irish language as a disposable part of Irish culture; nor did they believe in his complete dismissal of violence as a political lever. These men formed part of the ‘Young Ireland’ movement part of a wave of nationalism sweeping across Europe in the middle of the nineteenth century. A recent BBC 2025 TV series by the historian Simon Schama ‘The Story of Us’ 17 delves into the origins of the Romantic movement pioneered by poets like Shelley and Byron, where songs, art, poetry and literature were used as the inspirational fuel for popular political and social movements and its ongoing influence into the present day. (The Romantic movement itself was a backlash against the dehumanising effects of mass industrialisation and Enlightenment ideas).18

A thousand haranges…

However in O’Connell’s time most Irish cultural heritage was still a reflection of local connections or beliefs, there were few island wide cultural touchstones and even the Irish tricolour flag (an import from France in 1848) had yet to be widely adopted.Thus national songs suitable for service in the Irish independence political project were somewhat lacking and it was into this vaccum that Thomas Osborne Davis, a half Welsh Protestant from the town of Mallow in County Cork and Young Irelander, stepped. Davis strongly believed in the power of music to stir emotions and wrote:

a song is worth a thousand harangues19

But in 1841 thoughtfully chewing his pencil top whilst looking down the list of existing Irish songs, Davis must have crossed them off one by one with ‘Not warlike enough’, ‘Too sad’, ‘not anti English enough’. Not having found any suitable songs, Davis decided then to compose his own, set to traditional melodies. And that’s where the ‘The West’s Awake’ comes in because the song is obviously a first stab at a ‘How to Write a Song Which Will Make People Feel Irish’. Local placenames? Tick. Local Irish chieftains? Tick. Local landmarks? Tick. Battles? Tick, Tick. References to anti English sentiment? Tick, tick, tick.

But as I hinted at the start of this essay in some ways, the song is in many ways an interesting failure, since Davis must have soon realised that he’d spread his net both too wide and not wide enough. ‘The West’ was too nebulous a concept, if he’d stuck to ‘Galway’s Awake’ or ‘Roscommon’s Awake’ or alternatively ‘Ireland’s Awake’, it might have been more successful. Another drawback of the song is its tempo, a slow build to a crescendo usually sung by a solo singer. This means that it doesn’t lends itself easily to large groups of people singing together and it requires the audience’s sustained and quiet attention.

But Davis’s next try was the much more successful ‘A Nation Once Again’ which is to this day the unofficial Irish national anthem and (at least in my view) far more successful than the actual Irish national anthem, the solemn and not very hummable Amhrán na bhFiann, (translated as the Soldier’s Song)20. It contains the killer lyrics:

‘And Ireland once a province be, A Nation Once Again!’ 21

and the upbeat melody and tempo are ideal for large groups of people singing it en masse. It can be heard today belted out at St Patrick’s Day parades, GAA hurling and football matches as well as umpteen pub singing sessions. (It also lent itself deliciously to satire by the late Irish comedian Dermot Morgan in 1987 with his mick taking of Irish rebel songs ‘An Alsatian Once Again’)22.

Unfortunately Davis never saw this success as he died of scarlet fever at the age of 31 and the collapse of the Young Ireland movement itself followed shortly afterwards in the wake of a very short lived and tiny armed insurrection23. This might have meant that Davis’s songs risked going down in history as the nineteenth century’s equivalent of Kajagoogoo, i.e. a minor pop sensation in the 1980s24 who wrote a couple of mildly successful songs which quickly faded into obscurity, except for one thing; the event which turbocharged Irish national consciousness - the Great Famine of 1845-1851.

This event which was both a catastrophic failure both of the potato crop, and of British bureaucratic imagination meant that over a period of five years nearly two million people died or emigrated, and from which the Irish population levels never recovered25, put Davis’s song on steroids. It meant that people singing ‘A Nation Once Again’ after the Great Famine sang it in a way that no Irish song had ever been sung before, as a vessel to channel the resulting pain, grief and anger, a cultural gun aimed at the heart of the British political establishment.

Today’s performance cancelled due to cast members taking the script literally…

The nascent Irish independence project was boosted in the following years by the popular successes of ‘A Nation Once Again’ and its many imitiators, accompanied by other strands of the cultural independence such as the poetry, art and literature and which all contributed to the creation of a distinctively Irish consciousness. This was often invoked for political purposes such as the Land Wars of the late nineteenth century (which I have written about here) and the Irish Home Rule campaigns. The British State attempted some pushback by organising events such as Queen Victoria’s Royal Visit to Ireland in 1900 with the aim of fomenting loyalty to the British Crown and thus undermining the Irish independence movement.

It was in response to the popular acclaim the Queen received on the streets of Dublin in 1900 (shown here in some recently uncovered amazing footage26) that the poet WB Yeats and Lady Gregory wrote their famous play Cathleen ni Houlihan which made a veiled plea for armed insurrection against British rule. This play, which often featured society beauty Maud Gonne in the lead role, was regularly staged in Dublin for some years afterwards and it was due to run on Easter Monday 1916. The performance had to be cancelled as many of the cast and audience were out on the streets with actual guns doing exactly what the play had prompted- enacting a violent insurrection (perhaps the ultimate example of Method Acting as I have written about here).

Armoured cars and tanks and guns...27

1916 is, of course the key event in the mythology of the foundation of the Irish State, and several of its main leaders were published poets, such as Padraig Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh who were then executed for their part in it.28 The Irish War of Independence 1920-1922 which followed also produced many cultural products in its support, for example the song ‘The Foggy Dew’, which contrasted the many thousands of Irish soldiers fighting in World War One with those fighting in the Irish independence struggle against the British State - brilliantly sung here by Sinead O’Connor29.

Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Sulva or Sud-El-Bar 30

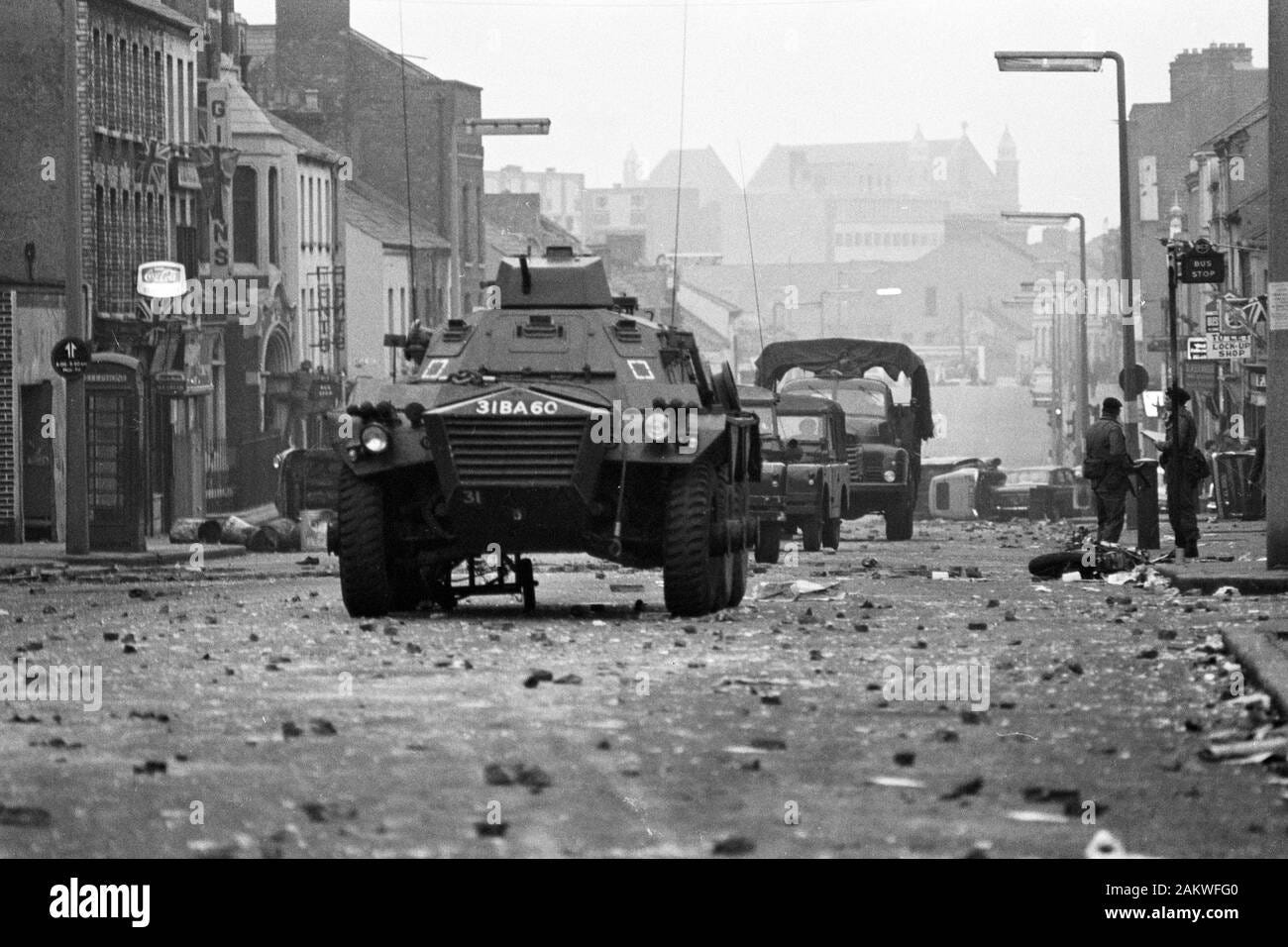

But after the South had achieved independence, these songs seemed to be nostalgic relics of the past with no contemporary relevance. This was not true in the part of the island still under British rule, Northern Ireland where the republican protest song‘The Men Behind The Wire’31 describing the British Army’s 1971 Operation Demetrius, picking up nationalist men for interment without trial starts with the electrifying line:

Armoured cars and tanks and guns, Came to take away our sons32

If a Nation Once Again was a cultural gun then ‘The Men Behind The Wire’ is more like a Uzi submachine gun spitting out unforgettable lyrics like ‘Cromwell’s men are here again’. Whatever your political views on the subject - it could not be denied that here the cultural power of music had been flexed to devastating effect and it spent months in the Irish hit parades. Its composer Paddy McGuigan received the ultimate accolade, he too because one of ‘The Men Behind The Wire’ he wrote about when he was put in prison without charge for three months in what was perceived as British State revenge for writing it. His lyrics are more relevant today than ever in a world where armoured cars and tanks and guns are still rolling out ‘wrecking little homes with scorn’ and justice is ignored ‘Not for them a judge or jury, Or indeed a crime at all’, but today these might be found in the Middle East or elsewhere.

Of course, on the Unionist side, the power of culture had always been equally important, marching Orange bands, Lambeg drums and flute bands are still formidable weapons to assert Unionist identity.33

If You Ever Go Across the Sea to Ireland…34

However since the Good Friday agreement in 1998, while both pro and anti British sentiment undoubtedly still exists on the island, most people North and South are too busy making a living today to worry about it. Many Irish songs since independence have been variations of the usual romantic tropes of boy-meets-girl, or in the 1950s and 60s evocations of the Irish emigrant experience like ‘Galway Bay’ written by Dr Arthur Colahan in 1947.

Later exceptions to this include the extraordinarily prescient 1979 song by Dublin band the Boomtown Rats ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’, the first about an American high school shooting which starts with the startlingly modern:

the silicon chip inside her head had switched to overload35

since this was long before the advent of personal computers or smartphones (it was inspired by the composer Bob Geldof’s work at the time with a young Steve Jobs). Another Geldof song ‘Banana Republic’ in 1980 is a savage attack on the continued influence of the Catholic Church and its alliance with political power in the Republic of the 1970s and 80s and lambasted the joint power of:

the black and blue uniforms, police and priests36

(This was of course long before the clerical scandals of the 1990s fatally undermined Church influence on Irish society in the Republic).

Geldof was not alone in his critique, the late Sinead O’Connor famously ripped up a picture of the Pope on primetime American television and suffered a huge backlash as a result37. Thus began a gradual unyoking of Irish politics and the Catholic religion in the Republic which had existed from the time of O’Connell which culminated in the recent passage of bills permitting gay marriage in 2015 and the repeal of the abortion ban in 2018. Cultural crtiques of the Church’s power have therefore been drained of much of their potency in recent times as its influence wanes.

I will Follow You….

Bob Geldof moved to London in the 1980s and his success there with his band the Boomtown Rats marked one of the first of a new breed of Irish bands finding fame outside Ireland. The most successful of these was the Dublin band U2 who became a globally renowned success from the nineteen eighties. In 1984 Geldof and Bono, the lead singer of U2, as well as a whole host of pop stars collaborated on the charity single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ prompted by Geldof’s outrage at a BBC TV News report on the victims of the Ethiopian famine:

we took an issue that was nowhere on the political agenda and, through the lingua franca of the planet – which is not English but rock ‘n’ roll – we were able to address the intellectual absurdity and the moral repulsion of people dying of want in a world of surplus38

This went on to be the hugely successful and influential ‘Live Aid’ international concert in 1985 where Geldof and his collaborators assembled an enormous collection of international music artists performing for free in two live concerts conducted simulaneously in London and Philadephia, all the proceeds going to famine relief efforts in Africa.

This was one of the first attempts to harness the cultural power of music for political ends: to shine a spotlight on conditions in the Global South and although critiques of ‘white saviourism’ have been been made about both BandAid and Live Aid39 - the power of culture which it harnessed to influence politics and public opinion has been much imitated ever since. Geldof explicitly linked the Irish response to these concerts to the Great Famine, saying in 2018 at the opening of an exhibition on the Great Hunger in Ireland:

When Band Aid and Live Aid happened, it was no accident that this country pro rata gave more than any country in the rest of the world. Of course, I’m a Paddy, so that has a lot to do with it. But more to the point, there was an immediate association of understanding of the horror and the consequences of that.40

Small hairs are rising on the back of every Irishman’s neck.….41

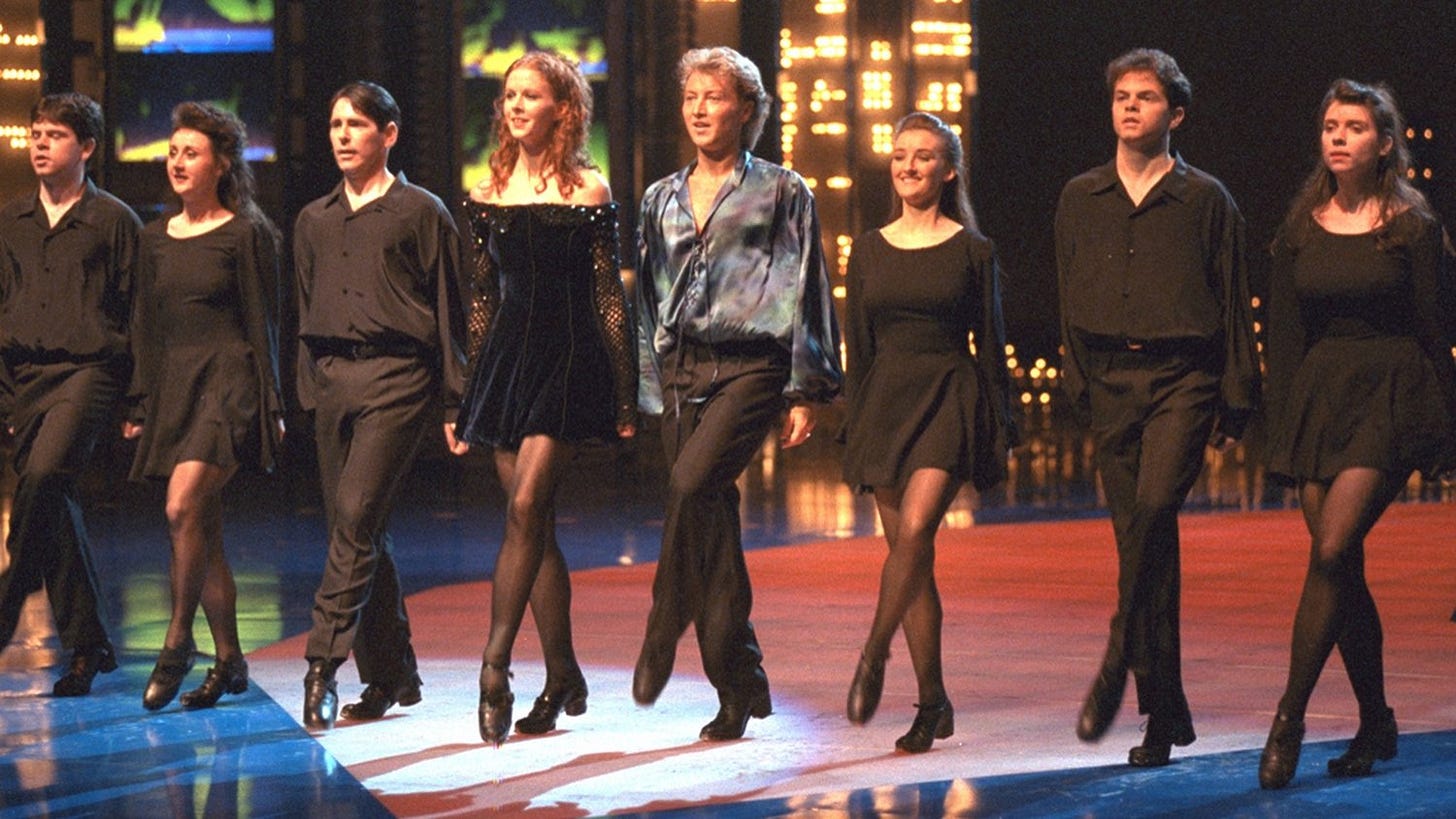

This is what the Irish BBC commentator Terry Wogan at the end of the interval act of the Eurovision Song Contest in Dublin in 1994 which featured the spectacle of a wall of hard shoed Irish dancers stomping and high kicking in synchronity and produced an enormous national collective intake of breath and delight (and drew tears from the Irish president Mary Robinson who was present42). From an outside perspective it seems peculiar that a short piece of stage entertainment should have elicted such a strong response, but Irish dancing had been for generations of Irish school children something that you did in school and quickly discarded under the influence of the siren song of global culture in your teens. That moment in 1994 was like finding that a picture hanging over your granny’s mantelpiece which you had never paid much attention to was actually a Rembrandt.

This resounding success expanded into the internationally successful musical Riverdance which has been pulling crowds around the world ever since. The plot line of Riverdance is the story of how the Irish, long oppressed in their own country by the British, went to America and rose to the top table of success by following the golden rules of capitalism, hard work and effort. A poster boy for this form of Irishness might be someone like Bernard Looney, who came from a small dairy farm in County Kerry to become the chairman of British Petroleum in 2020, one of the largest and richest fossil fuel companies on earth (but who resigned in 2023 after allegiations of impropriety).43

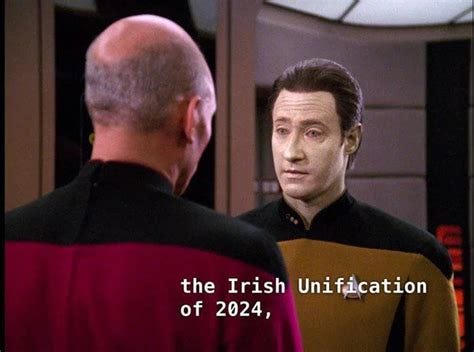

Since Riverdance the Irish so long the underdogs of Europe are - as I remember the Irish actor Liam Neeson saying back in 1998- ‘having a moment in the spotlight…it is our time,’ and neither our accents or backgrounds are seen as drawbacks in the boardrooms of international capitalism as the career of Looney and many others show. Even a resolution to the seemingly intractable problem of Irish unity may be on the horizon (as a 2007 episode of the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation predicted would happen in 2024) as the demographics of the island slide more towards nationalism (although as one of my correspondents predicted probably not without violence - the Unionists aren’t going anywhere yet anytime soon).

It would be easy to see all of this as a vindication of Davis and Pearse’s visions, that Ireland is now ‘A Nation Once Again’ and we have no more need of songs to rally us against an external aggressor or to assert our independence. Instead we can sit back and pat ourselves on the back that our ancestors would be proud of the new multi ethnic, tolerant, rich and successful Ireland of today. Rebel songs now provide a warm bath of nostalgia, an evocation of the Bad Old Days When We Were Poor. Our pubs are now scattered across the globe, our culture is celebrated on Broadway stages, our actors are honored in Hollywood, our literature is valorised, to be born Irish today is to be One Of The Winners of global society. David McWilliams said in his 2005 book ‘The Pope’s Children’:

Ireland has arrived…We are now a middle class nation 44

In your face, Belgium!45

The TV cartoon series ‘The Simpsons’ is a cultural phenomeon which has been sometimes eerily prophetic, famously foreshadowing the presidency of Donald Trump in the year 200046. In their 2009 episode, ‘The Name of the Grandfather’ the Simpsons came to an Ireland populated by American multi nationals, with latte-sipping locals who are too busy to go to the pub47. So is there any truth in their portrayal and how does today’s iteration of Irishness look?

One way of judging this might be to look at the visual landscape of Ireland. Much of modern Ireland’s architecture shows little evidence of a particular locality or attachments. Most of the new buildings on Dublin’s docklands could just as easily be lifted from downtown Manhattan or Chicago and the motorways which link the main cities on the island bypass small Irish towns full of shuttered shops. The 7,000 Irish pubs scattered across the globe are sometimes situated in genuine Irish disapora communties, but more often in my experience, are just an ertaz Irishness, staffed by people who have never set foot in Ireland pulling pints of Guinness under fake road signs to tiny Irish towns whose names they can’t pronounce.

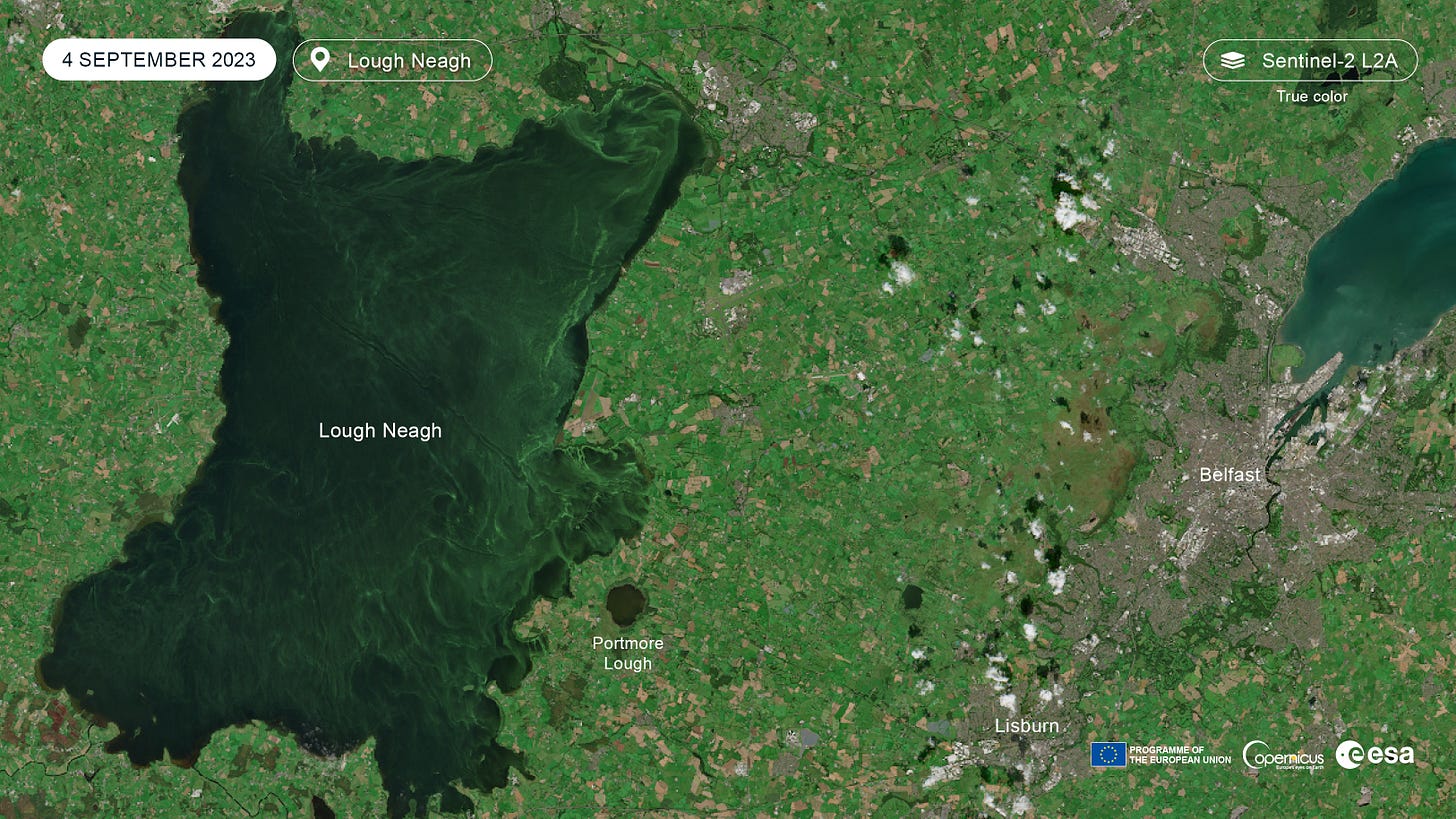

In the meantime, back on the island of Ireland itself, natural jewels like Lough Neagh in the North of Ireland are now virtually dead and even places like Killarney National Park are being destroyed by invasive species like rhodedendron and feral goats48. Many Irish work today, not on the land, but for large American multinationals attracted by Ireland’s low tax rates49. The housing crisis means that many young Irish struggle to afford a decent place to live50 and Ireland has also become a hub for European capital of data centres51, vast computer farms who suck up to a fifth of the island’s electricity grid. There is a health care crisis, despite the construction of hugely expensive projects such as new children’s hospital in Dublin (at a staggering 1.2 billion euro making it the most expensive on the planet52) but around the country A&E departments are overflowing53. Political life is fractured, with corruption and policies on mass immigration and the evisceration of public services generating rising popular anger54.

They weighed so lightly what they gave...55

There is minstrelsy of birds

In Glenasmole,

The blackbird and thrush

Chanting music (On the Strand of Howth, 1916)56

So in a thought experiment what would Padraig Pearse, the executed leader of the 1916 rebellion- whose poetry was suffused with love for the Irish natural world- make of modern Ireland? It is difficult to believe that he would view the catastrophic decline of Irish wildlife across the island with anything other than indignation and anger57. He had a particular love for Connemara and its landscape; I cannot imagine that he would see the recent proposal to site 30 wind turbines, each as high as the Eiffel Tower, in some of the most beautiful seascapes in Europe with anything other than dismay (which I have written about here).

You might dismiss Pearse as a romantic, but there is another figure from Irish history whose opinion on modern Ireland I would dearly love to hear: Michael Collins58, one of the chief architects of independence (tragically killed in the Irish Civil War in 1922) was a hard headed realist who correctly identified that the real goal of the British Empire (and indeed of all Empires from the beginning of time) was actually economic, that the violence and the propaganda was all in service of economic exploitation.

The history of this nation has not been, as is so often said, the history of a military struggle of 750 years; it has been much more a history of peaceful penetration of 750 years. It has not been a struggle for the ideal of freedom for 750 years symbolised in the name Republic. It has been a story of slow, steady, economic encroach by England. It has been a struggle on our part to prevent that, a struggle against exploitation, a struggle against the cancer that was eating up our lives, and it was only after discovering that, that it was economic penetration. that we discovered that political freedom was necessary in order that that should be stopped…..Our strength as a nation will depend upon our economic freedom59

But if Collins were alive today, I could see him striding around Dublin’s docklands, waving in the direction of the steel and glass skyscrapers and demanding in his Cork accent ‘who owns that, and that, and that?’. He would find the answers in the recent book by Matt Cooper ‘Who Owns Ireland?’ (2023) as it delves into the shocking extent to which the country’s land and property have been captured by international financial interests, and in particular by large American asset management companies. But after reading it, I could see him narrowing his eyes and saying ‘did you people just exchange the British for Global Capital instead?’ And it would be difficult to refute his accusation, as the present sucessors to the long defunct British Empire are in my opinion the global companies which make up, in my view one of the most rapacious Empires in human history. Frantz Fanon also points out in his 1961 book ‘The Wretched of the Earth’:

For a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.60

There is pockets of hope, Ireland still possesses a vibrant native culture with amateur sports like hurling thriving, the Irish language undergoing a renaissance, and the cultural scene is still vibrant. But the promotion of the Irish to the global world stage masks an uncomfortable reality - that stage is built on the the labour and exploitation of the peoples of the Global South and the devastation of much of the planet.

The Pope’s Children…61

This brings me back to ‘The West’s Awake’, and its relevance today. I have often wondered why Davis, a Cork man who lived most of his short life in Dublin, chose ‘the West’ as his subject for a song, and also why my father found it so appealing. I would like to suggest some possible answers, although they can only be speculative because we can’t ask either of them. The West of Ireland was, despite its stunning natural beauty, its most despised part for many years. It was the place considered so useless that even Cromwell didn’t bother conquering it, the home of the dispossessed - the refugees from elsewhere in Ireland as I have written about here. It was (and probably still is in some quarters) considered by the Dublin elites as a place populated by the uncouth and uneducated.

The word ‘culchie’ in Ireland comes from the small County Mayo town of Kiltimagh and is still used as a derogatory term for anyone from rural Ireland, meaning the Irish equivalent of the Appalacians, a place full of rednecks, attracting the snickering derision of their Dublin/Washington counterparts62. That laughter may have largely died down in Dublin recently since the boardrooms of many international companies are now staffed by the sons and daughters of rural Ireland, and the Bernard Looneys of this world are no longer held back by their backgrounds or accents, many of them successfully navigating universities and international boardrooms to ascend the ladder of global success; ancestral shame washed away by expensive suits and large paypackets. This cohort, many of whom were conceived around the visit of John Paul II, to Ireland in 1979 (hence the ‘Pope’s Children’), formed part of the first generation in Irish history since the Great Famine where the population expanded. This was extensively discussed in the 2005 book by Irish economist David McWilliams where he said that:

Ireland has arrived….we are better off than 99% of humanity63

The oppressed will always believe the worst about themselves…64

In 1961 the philosopher Frantz Fanou wrote a seminal book on French cololonism in Algeria called ‘The Wretched of the Earth’ in which he says that:

Colonialism hardly ever exploits the whole of a country. It contents itself with bringing to light the natural resources, which it extracts, and exports to meet the needs of the mother country's industries, thereby allowing certain sectors of the colony to become relatively rich. But the rest of the colony follows its path of under-development and poverty, or at all events sinks into it more deeply65

The West in Ireland was exactly that part of the country which received least attention from its coloniser- the British Empire- but it was also the part which retained much of its original identity. It was thus possibly seen by Davis, and Pearse after him as the repository of the original pre colonial culture, the home of the ‘real’ Ireland. Fanon also talks in the book about the psychological effects of colonisation, the need for the colonised to deny the power dynamics of their real situation as survival strategy, since to challenge the existing order is too dangerous. As Fanon points out:

Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it.66

Thus the colonised must exist in a constant state of dissasociation where the real facts of their situation are pushed into their subconscious awareness, to remain in the words of ‘The West’s Awake’67:

slumbering slaves ..

I would argue that for many years in Ireland, as well as being subjects of the British State, the Irish were also subjects and colonised by the Catholic Church and they remained so after independence, with only a brave few such as the writer James Joyce, or Sinead O’Connor willing to call out the psychological oppression that the majority had collectively decided to suppress for the sake of consensus; it came at a high personal cost for both of them. Both are now fully rehabilitated in public opinion, Dublin proudly celebrates Joyce’s Bloomsday each June and O’Connor in particular has being feted for her early courage in confronting the Church68.

What those who now are busy praising her (but who in her lifetime, in her words viewed her as ‘a madwoman in the attic69’ ) often fail to notice is the other vested interests which O’Connor took on and for which she paid a higher personal price. For instance, O’Connor refused to have the US national anthem played at her concerts, a decision which resulted in her getting banned from many US venues, and which drew in 1990 the following comment from Frank Sinatra:

This must be one stupid broad. I’d kick her ass if she were a guy70

She also correctly identified the capture of the music industry by big business corporations and its monetisation of misogyny in her searing open letter to the singer Miley Cyrus in 2013:

The music business doesn't give a shit about you, or any of us. They will prostitute you for all you are worth, and cleverly make you think its what YOU wanted……You are worth more than your body or your sexual appeal……If you have an innocent heart you can’t recognise those who do not.71

But while it is now perfectly safe to criticise a largely defanged Catholic Church in Ireland today, widespread criticism of the US -given the number of large multi national global corporations which are dotted around Ireland- is a far riskier affair, so this part of O’Connor’s legacy tends to be quietly ignored.

Aut Zuck, aut Nihil..

Frantz Fanon also wrote in his 1961 book ‘The Wretched of the Earth’:

Two centuries ago, a former European colony decided to catch up with Europe. It succeeded so well that the United States of America became a monster, in which the taints, the sickness and the inhumanity of Europe have grown to appalling dimensions72

The Catholic Church (which of course means universal church) is more usually referred to as the Roman Catholic Church, and in many ways, it could be seen as a present day outcropping of the Roman Empire with Latin as its official language73. Another fan of Latin and the Roman Empire is the head of Meta Mark Zuckerberg who has recently taken to wearing a T shirt with the Latin motto ‘Aut Zuck, aut Nihil’, which might translate roughly as his wish to be seen as ‘Either a Caesar, or nothing’ and his admiration for the Roman Empire has extended to calling his children after Roman Emperors74.

But the 2002 book ‘Jesus and the Empire’ by Richard Horsley describes what living under Roman occupation in first century Judea was really like; a brutal police state where the land and peasantry were ruthlessly exploited but also where the native population had to participant in a type of mass hallunication as a survival strategy, as even a hint of dissent risked a painful and humilitating public death: crucifixion (an interesting example of this may be the Biblical story about the man whose demons were called Legion (hint,hint), and the resultant panic of the community after he was healed, they couldn’t get Jesus out of town quickly enough in case the Romans showed up).75

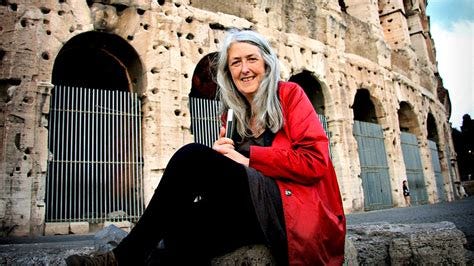

The Roman Empire was thus in this view not only a physical entity, it also thoroughly colonised the minds of its subjects. It could be argued that Roman influence over popular consciousness extends to the present day; Roman law forms much of the basis of common law, and Rome is regularly referenced in culture, from Shakespeare to Monty Python, and everyone from the Victorians to the present day measure the decline of civilisation against the supposed demise of Rome. But as Dr Mary Beard recently pointed out in her 2016 BBC TV series: Ultimate Rome: Empire Without Limits76 (I do love that woman) few voices from Rome’s subject populations are ever heard. But the voice of Calgacus in 83 AD from the Scottish lowlands rings out down the millenia777879. He said of the Romans:

Robbers of the world, having by their universal plunder exhausted the land, they rifle the deep. If the enemy be rich, they are rapacious; if he be poor, they lust for dominion; neither the east nor the west has been able to satisfy them. Alone among men they covet with equal eagerness poverty and riches. To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace80

(and this is what Zuckerberg admires???).

The maintenance of this narrative in the population, as Horsley discusses, was often done by elite classes such as the journalists Pharisees who in return were allowed greater wealth and freedom than the bulk of the population, but who were also effectively intellectual collaborators with their oppressors (as a result their portrayal in the Gospels is a synonym for hypocritic)81 - Fanon also describes the same dynamic in twentieth century Algeria82:

The national bourgeoisie discovers its historical mission as intermediary. As we have seen, its vocation is not to transform the nation but prosaically serve as a conveyor belt for capitalism, forced to camouflage itself behind the mask of neocolonialism.

Yeats, in his despairing poem September 1913 (associated with the aftermath of the huge strike called the Dublin lock-out) describes the same dynamic amongst the Dublin middle classes pre independence:

What need you, being come to sense, But fumble in a greasy till…Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone, It’s with O’Leary in the grave.83

But, from time to time, an individual from the most oppressed and exploited classes, like Jesus, would step out from the dominant narrative and speak truth to power, pointing out the injustice of the existing social order, in what Horsely refers to as ‘the peasant’s roar’84. This didn’t end well for Jesus, or for others such as Pearse, Gandhi and Martin Luther King who have performed the same role elsewhere, but their fates can often act as a cataylst for the remainder of the population to wake up from their collective hallunication85.

The wretched of the earth…

Maybe that is what Davis was trying to do in the song ‘The West’s Awake’; to rouse the Irish from their collusion with the occupying power (at that time the British State) warning them that they were all ‘in slumber deep’. But the poorest and most oppressed haven’t disappeared, instead they might be found today in the child miners of the Congo, or under the bombed out buildings of the Middle East - today’s wretched of the earth - in 1984 Geldof saw them in the victims of the Ethiopian Famine. Davis also points out in other lines of ‘The West’s Awake’, that in the end, oppressors and oppressed both, we are all subject to the power of Nature:

Sing, Oh! Let man learn liberty, from crashing wine, and lashing sea86

And maybe that is also why my father loved the song so much. It is a riposte to Those Who Thought We Were Stupid, a reminder that the local, the rural, the small, the despised are valuable, that their lives are as important as those who aspire to rule over them by virtue of supposed superior cleverness, education or sophistication and that the land belongs by right to those who live on it and love it, not to those who see it only as an economic asset to milk.

The recent events in the Middle East and the elevation of Donald Trump to the White House may also be the catalyst for the rest of us in the Global North to wake up and realise that we have all been colluding in the narrative of unlimited consumption, run away consumerism and thereby unconsciously propping up a worldwide inhuman regime which is destroying the only home we have.

In truth when he was alive I found my father’s choice of ‘The West’s Awake’ slightly bemusing and often even a little embarrassing, but as his coffin left the thronged rural Irish church accompanied by my cousin’s beautiful solo rendition of the song; it transformed for me into a powerful evocation of the man and his unashamed pride in coming from a particular place, a place he was born, worked in all his life, brought up his family in, and spent his life serving his community, all in a radius of under five miles. I don’t think there was a dry eye in the church. Thanks Dad, this is for you.

Post script:

I have come across the following song written in 2006 written by the British indie group Razorlight, which in the light of recent events there seems to channel the dystopian vibe of what’s currently happening. Also some of the section headings I have introduced into the text are from Yeats’ despairing poem about the complacency of the Irish middle classes pre 1916, the poem September 1913 ‘fumbling in the greasy till’. He could, in my opinion, be writing it today.

https://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/irish-songs-ballads-lyrics/wests_awake.htm

https://medium.com/@allgoodtales/how-the-skibbereen-eagle-kept-a-watchful-eye-on-the-czar-of-russia-5d64d4b75fed

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=The+West%27s+Awake&atb=v273-1&iax=videos&ia=videos&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DV1xD1UwhKqg

in West Cork and the neighbouring county of Kerry they were (and are) geniuses at turning the usual cosmopolitan derision aimed at country hicks right back against their adversaries- for instance the Healy Rae political dynasty in neighbouring Kerry has brought this to an artform with their deliberate thumbing their noses at their Dublin counterparts and have practically wrote the How To Get A Rise Out of The Dublin Media playbook. This is known in this corner of the world as being ‘a cute hoor’ (nothing to do with women).

https://richarddawkins.com/books/book/the-selfish-gene

https://1library.net/article/the-historical-construction-of-irish-national-identity.y8gllr4z

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57309/september-1913

ibid

https://academic.oup.com/ereh/article/24/3/522/5669868?login=false

https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/research/spotlight-research/what-19th-century-travel-guides-had-say-about-ireland

https://archive.org/details/ethnicamericahis00thom

https://www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/ireland/peelire.htm

https://liberalhistory.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/124-McGowan-The-Liberator-and-the-Grand-Old-Man-1.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_O%27Connell

http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/o/OConnell_D/comm.htm

https://allpoetry.com/The-Harp-That-Once-Through-Tara's-Halls

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=The+story+of+us+simon+schama&atb=v273-1&iar=videos&iax=videos&ia=videos&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.dailymail.co.uk%2Fvideo%2Fuknews%2Fvideo-3353161%2FVideo-Watch-trailer-BBC-documentary-Simon-Schamas-Story-Us.html

Davis was a proponent of what would be called cultural nationalism, a movement sweeping across Europe in the mid nineteenth century, the idea that nation states had distinct cultural identities expressed in unique local culture patterns such as folk tales, songs and poetry. One of the originators of this and the original Bad Boy Whom Girls Love was Lord Bryon, himself heavily influenced by the songs of the Irish composer Thomas Moore (they were close friends), and immortalised in the phrase mad, bad and dangerous to know. Byron was heavily involved in the campaign for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire and he sold his family estate to finance it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Nation_Once_Again

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amhr%C3%A1n_na_bhFiann

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Young-Ireland

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/famine_01.shtml

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-35873316

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=sinead+o+connor+the+foggy+dew&atb=v273-1&iax=images&ia=images

ibid.

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=The+Men+behind+the+wire&atb=v273-1&iax=videos&ia=videos&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DwH8_jdZKG2E

What ever your political persuasion, you can’t deny the power of lyrics like ‘Cromwell’s men are here again’. Proving yet again that Upsetting The Irish is a Really Bad Idea, as we will wait for centuries if necessary to get our own back. And it’s composer was paid the dubious compliment of being imprisoned for three months, for the crime of writing it!

https://bobmcevoy.co.uk/2018/07/13/the-auld-orange-flute/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sinead-OConnor

https://www.today.com/popculture/u2-coldplay-among-bands-play-live-8-wbna8046322

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/bob-geldof-white-saviour-live-aid-b2497269.html

https://www.irishcentral.com/news/famine-beginning-of-irish-nation-geldof

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/riverdance-eurovision-1994-video-ireland-irish-dancing-michael-flatley-butler-a8888841.html

https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/television/former-president-mary-robinson-was-moved-to-tears-by-riverdances-famous-eurovision-1994-performance/31210225.html

https://www.ft.com/content/65837ce0-57cd-4db6-8de7-af190c37f77c

The Pope’s Children, 2005, David McWilliams, Gill and McMillian

https://screenrant.com/simpsons-donald-trump-president-prediction-episode-bart-future/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_the_Name_of_the_Grandfather

https://www.irishnews.com/life/stunning-images-capture-irelands-disappearing-beauty-ZOMUGE3QHVA43IWIWDFLBLTGVQ/

https://www.ft.com/content/46e44b6c-c203-11e2-ab66-00144feab7de

https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/2024/08/15/housing-irelands-population-is-growing-at-nearly-four-people-for-every-new-home-built/

https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2022/0815/1315804-data-centres-ireland-electricity-energy-resources-climate-change/

https://www.rte.ie/news/2024/0601/1452380-childrens-hospital/

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/broken-ireland-s-ailing-health-service-1.2340468

https://www.politico.eu/article/government-ireland-independent-michael-martin-group-riggers-verona-murphy/

September, 1913 WB Yeats

On the Strand of Howth, Padraig H. Pearse, 1915

https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/editorials/2024/10/02/the-irish-times-view-on-the-irish-environment-a-deepening-crisis/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michael-Collins-Irish-statesman

http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/treaty/treaty-debate-michael-collins-speech/

‘The Wretched of the Earth’, Frantz Fanon, 1961

The Pope’s Children, David McWilliams, 2005

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culchie

ibid

https://dn790007.ca.archive.org/0/items/the-wretched-of-the-earth/The%20Wretched%20Of%20The%20Earth.pdf

ibid

The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon, 1961

https://genius.com/Thomas-osborne-davis-the-wests-awake-annotated

Sinead Bernadette O Connor was named after the wife of the arch conservative Eamon De Valera and St Bernadette of Lourdes.

https://www.radiotimes.com/audio/radio/sinead-oconnor-radio-4-womans-hour-newsupdate/

https://www.grunge.com/986575/frank-sinatra-had-some-brutally-honest-words-for-sinead-oconnor/

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2023-07-28/sinead-oconnors-2013-letter-warning-miley-cyrus-that-nudity-would-obscure-her-talent-goes-viral-again

ibid.

https://vatican.com/The-Roman-Empire-and-the-Vatican/

https://www.businessinsider.com/mark-zuckerberg-viral-roman-empire-meme-kids-named-for-emperors-2023-9?op=1

https://divinenarratives.org/the-meaning-of-legion-in-biblical-and-historical-contexts/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0797yqk

one of the few places where in modern parlance the Romans got their asses handed to them and had to retreat - the very place where most of the Ulster Scots came from many centuries later

https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/why-couldnt-the-romans-hold-and-conquer-scotland-1470559

https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/readings/agricola.html

The Romans never came to Ireland, supposedly because the weather was so bad, they christened the island ‘Hibernia’, translated ‘Winter’, which sounds to me like a classic piece of black propaganda (we didn’t invade coz it was too cold guys!) the real reason might have been that they got so badly burned by the Scots they decided to cut their losses rather than face their equally fierce Irish cousins.

https://www.thesaurus.com/browse/pharisee

The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon, 1961

September, 1913, WB Yeats.

https://brill.com/view/journals/jshj/8/2/article-p99_1.xml

ibid

https://www.irish-folk-songs.com/the-wests-awake-lyrics-and-chords.html

Insightful and informative! A brilliant history revision and commentary on contemporary world politics. Thank you. 👍

Brilliant essay. Thanks