In these occasional idiosyncratic thought pieces I am exploring some general themes about the cultural and social techniques used by the British Empire to impose hegemony through the lens of (mostly) Irish history, and also the varied means of resistance that the Irish used to push back. I will also try and link these with some of our current ecological dilemmas and whether there are any lessons from history that may be applicable. If any of these essays sparks further interest, then I may do a ‘deep dive’ in a more academically focused essay. But feel free to comment!

My grandfather used to say that ‘All you need for a good life is your own bit of ground’. He and his wife brought up six children on a largely self sufficient small farm in rural Ireland in the nineteen forties. He lived into his nineties, and I have vivid memories of his funeral, where, because he had participated in the 1916 rebellion, there was a military gun salute over his grave. He was a quiet man, he never talked about this, or about politics in general, to his family. He was unimpressed with many of trappings of modernity, but loved animals and the nature which surrounded him in rural East Galway.

Land ownership has always meant something different in Ireland. In much of the UK, large tracts of the countryside are still under feudal ownership1. Since much of the population (at least in England) is urban, and until recently, Ireland was a largely rural self sufficient land dwelling society, this has mean a marked difference in attitudes to land ownership between the two countries. Although many rural Irish have now migrated to the urban centres of Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Galway, few are more than a generation away from memories of growing up in the countryside.

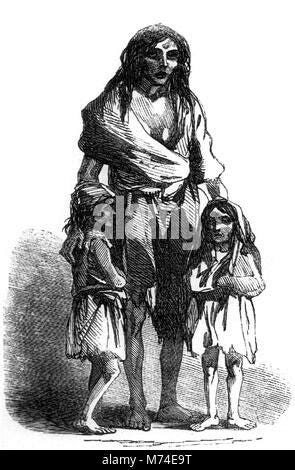

My grandfather was not alone in his attachment to the land, rural Ireland is full of tales of bitter feuds over small, often uneconomic pieces of land such in John B Keane’s famous play ‘The Field’ . These are sometimes difficult to explain to other audiences, but easy to understand when you grow up in a society like Ireland that is still living under the shadow of the existential crisis which was the Irish Famine of 1847-1851, where in the space of very few years nearly two million people died either directly or indirectly of starvation or disease, and which started a drastic shrinkage of the population through emigration from which it has still not recovered nearly two centuries later and which has only halted in recent years. Ireland, alone of all European nation states, still has a population less than it had in 18452.

Historians might argue the simple narrative commonly believed in Ireland about ‘the English let us starve’ is factually correct or not3, but the perception that the British state was perfectly happy to allow millions of Irish individuals to die rather than accept a change in economic policy, is one deeply bedded in the Irish psyche. And it is hard to argue against the reality that the British state, a modern industrial nation with vast wealth in the mid nineteenth century, permitted either by neglect, or poor management, the mass starvation of the best part of two million people on its doorstep within the space of ten years, and that at least some of those in power at the time regarded this as a good thing, as they viewed the Irish as ‘less valuable’ than the rest of the population on the British Isles. In a classic bit of victim blaming, Charles Trevelyan, the British civil servant most identified with this callous attitude said of the Irish:

‘The great evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people’.4

The emotional wake of this is still being played out in Irish society in my view, in my grandfather’s generation it manifested itself in the belief that ultimately, one could only depend on one’s ability to produce for yourself and your family, a distrust of the state and a determination not to put yourself at the mercy of distant power. And since the land was seen as the main way of feeding yourself and your family, it was tantamount to survival. It is my belief that the Irish independence movements was rooted in the widespread belief post Famine, that the Irish could only depend on themselves for their ultimate welfare and therefore needed to wrestle back control of their destiny, and their resources back from their distant overlords; and there is now some evidence to support this, that there was a corelation between support for independence in specific areas with how badly that area had been affected by the Famine5.

But long before the early twentieth century struggle for political independence, there was a large non violent resistance movement which focused on transferring the ownership of the land back to the tenantry. This played out across Ireland, but East Galway in particular was a hub of activity during the late nineteenth century, and a local organisation, the Ballinasloe Tenants Defence League became the template for the hugely more influential Land League which spear headed the successful campaign to buy back the land from landlords6.

When the exasperated British State tried to ‘kill Home Rule by kindness’,7 and the demand for political independence,by enabling the transfer of the land back to the Irish in various Land Acts during the late nineteenth century, they were sorely disappointed. During the Irish Land Wars, large numbers of the population had become used to regular participation in political organisation, performative protest, strategic participation in parliamentary disruption and generally gumming up the mechanisms of power. The Irish peasantry was no supine partner in this, and along with their upper class legislative allies like Parnell, they managed through through tenacity and determination to wrestle back from the occupiers that which had been taken two centuries earlier at the point of a gun although the land annuities were still being paid long after independence.

Although the transfer of land ownership also owed much to the economic collapse of many estates, ultimately it came down to a failure in British will to prop up the hegemony of the Anglo Irish in the face of sustained grassroots pressure. Once the Imperial spell was broken, rather than being appeased, the success of the Land Wars awoke something else in Irish society and emboldened other strands of Irish consciousness. I do not believe it was a coincidence that the Celtic revival of the turn of the twentieth century followed in the wake of the Land Wars. 8

Of course the Irish were, and are not now, a homogeneous mass, they contained a number of classes with diverging interests. It is debatable as to whether the ultimate beneficiaries of the Land Acts were not the rural poor, but instead the shop keeping mercantile classes who saw opportunities to make money from the demise of the aristocracy. A recent superb book by Myles Dungan ‘The Land is All That Matters’ examines this in more detail. In this, he examines the inter class aspect of the land question, and the extent to which the property owning native Irish both took advantage of the aftermath of the Famine to enrich themselves at the expense of their poorer neighbors (something I have noticed myself in the post Famine census), and the post independence capture of the nascent Irish state by these interests in defiance of the original ideological aims of the 1916 revolutionaries.

Land is all that Matters….

The question is what has this to do with today? And what lessons can we learn, if any from a long gone agrarian struggle? How could we resist today’s Empires of trans national corporations and aggressive macro states?

Firstly it should not be forgotten, as Dungan lays out in his magisterial book, that in the wake of an enormous national tragedy, a small largely rural population on the fringes of Europe, had within the space of 100 years by peaceful means and sheer persistence taken back the ownership of their native land whilst living under the heel of one of the most powerful Empires in world history at the peak of its power. That this should be a cause for enormous national pride is something perhaps not often appreciated in Irish history, and that this was largely an achievement of rural Ireland, should give pause to those presently living in urban Ireland who hold a dim view of the political sophistication and nous of their country cousins. It was the peasant farmers of rural Ireland who drove the British Empire to concessions that it had never made before, not their urban counterparts. That some of this resistance might not have been pretty, the possibility of rape, murder and violence was always on the table, as Dungan points out, does not invalidate their achievement.

The most significant part of this was the development of a variety of non violent protest methods, like boycotting, mass political organisations and media campaigns most of which are still being used today, and were widely taken up by other nationalist campaigns 9. They also took the battle to the aggressors, turning the tools of Empire back on themselves; using tools like filibustering and parliamentary obstructionism in the House of Commons10. Most importantly in my view the Land Wars also offered an ideological and spiritual counter to the prevailing economic orthodoxy of the times, land was equated with life sustaining resources and natural justice, rather than just another economic asset.11

Down the Old Bog Road…

For my grandfather, the value of his ‘bit of ground’ was not only economic, but also its emotional importance to his whole identity; it was a symbiotic relationship, loyalty and love was given to a particular piece of countryside in gratitude for the gifts it had bestowed on him. And on a wider scale, his view that this loyalty extended across the whole island and that outsiders had no right to steal the bounty of the land from those who loved it. He never spoke of why he had taken up a gun in 1916, and was completely uninterested in politics for the rest of his life; he remained a quiet countryman, focused on his family and farm. The only comment he was heard to make was about the pointless and futility of the Civil War ‘what the Irish did to the Irish was worse than what the British did’, but he never expressed any regret about wanting independence and kept his rock solid conviction that Ireland belonged to the Irish.

In my opinion the Land Wars underscore on a societal scale the importance of possessing the natural resources of a country in the maintenance of national consciousness, pride and nation building. It asks the question of how foundational that ownership, or the possibility of it is to the self determination of a society which wishes to be independent of outside domination and manipulation by others. This is perhaps a lesson that the modern Irish may be in danger of forgetting,12 but which worldwide smaller weaker states are now learning to their cost. Today’s Empires don’t need armies if they have ownership of key natural assets and infrastructure.13 Hegemony can be thus be exerted through the indirect leverage, rather than through military means, it can also be exercised by reducing the natural resources of a country to fungible economic units, rather than as inter generational treasures of inestimable value which can be most valued by those with an ongoing commitment to their nurture and preservation.

Above all, I believe the lesson from the Irish Land campaign is hope, hope that as the British Empire was not invincible then, neither are today’s Empires, that what is taken, can always been taken back and built upon. We are the inheritors of that hope, and perhaps it should make us reflect that if our ancestors could act thus in the wake of an unimaginable disaster, then may be we should act today to try and prevent another.

https://whoownsengland.org/2018/06/22/more-landowners-revealed-in-our-updated-map/

https://brilliantmaps.com/potato-famine/

https://archive.org/details/irishcrisis00trev/page/2/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/irishcrisis00trev/page/2/mode/2up

https://www.irishtimes.com/history/2023/03/02/great-famine-and-irish-independence-struggle-linked-by-geography-and-history/

https://tlio.org.uk/michael-davitt-and-the-land-league-an-irish-revolution/

https://centenariestimeline.com/1891_KHR.html

https://academic.oup.com/histres/article-abstract/89/243/88/5602996?login=false

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-50737-2_4

https://www.libraryireland.com/IrishIndependence/39.php

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/historical-journal/article/right-to-life-the-right-to-nature-and-the-impact-of-irish-land-on-political-thought-in-the-1880s/5B9766F01D59B7F067D68BB18C1AB8D1

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/who-owns-ireland-by-kevin-cahill-hidden-truth-of-land-ownership-in-ireland-1.4684193

https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Chinese-companies-corralling-land-around-world