Father Peter Lonergan: [narrating] Well, then. Now’. I'll begin at the beginnin'. A fine soft day in the spring, it was, when the train pulled into Castletown, three hours late as usual, and Himself got off. (The Quiet Man, 1952)1

(I am still experimenting with the mix of music and text in these essays; I recommend clicking on the footnote which has an accompanying track for each section beforehand - feedback welcome)

One of my guilty pleasures is John Ford’s 1952 romantic comedy ‘The Quiet Man’ starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara about a returning Irish American emigrant who falls in love with a local girl. There is plenty to dislike in the QM seen through modern eyes as it is full of the usual Irish drinking/fighting stereotypes and includes some shocking misogyny. But somehow I have a soft soft for it, probably at least in part because of the beauty of its West of Ireland setting lovingly portrayed in the Oscar winning cinematography of Winton C. Hoch and Archie Stout.

The QM seems to exist in a kind of time warp - on the one hand the costumes are from 1920s (after the establishment of the Irish Free State) - but in the film’s fictional village of Inisfree the local IRA either haven’t got the memo that the British are gone and they can disband, or if they have, are ignoring it. This is established right from its opening lines where the train is ‘three hours late as usual’ implying that in Ireland the railways - which in the rest of the world were bywords for punctuality and reliability - operated in a dilatory, haphazard kind of way (and thus adding weight to the impression that Inisfree itself exists in a time bubble). This is reinforced towards the film’s end when the heroine tries to run away to Dublin but is foiled because - eyeroll - as usual the train is late (four and a half hours this time).

Do You Think That We’ll be There Before The Night? …..here

‘The Quiet Man’ wasn’t the first to lean into the supposed dilatory Irish railway time keeping trope - one of its first and most celebrated appearances was in the nineteenth century comic song by the Irish composer Percy French ‘Are You Right There, Michael?’ available here (and which I will abbreviate as AYRTM as I’m too lazy to keep writing it in full - hey, I’m Irish, after all).

The story behind AYRTM is that on Monday the 10th of August 1896, Percy French, its composer, was on his way to Kilkee by train from Sligo (a distance of roughly 250 km) to give a musical performance in a local hotel. French was on the West Clare narrow gauge when - only miles from his audience - he sat in frustration for five hours without explanation in a railway carriage behind a broken down engine. When he eventually arrived breathless at Moore’s Concert Hall in Kilkee, it was deserted; his audience having gone home and with them, his anticipated earnings.

French then sued the West Clare Railway for the loss of earnings: £10 - which they refused to pay him. This act of corporate pettiness inspired French to pick up his pen and write the comic song AYRTM. Nineteenth century music hall audiences across the British Isles rocked in laughter to lines like:

You may talk of Columbus's sailing

Across the Atlantical Sea

But he never tried to go railing

From Ennis as far as Kilkee

You run for the train in the morning

The excursion train startin' at eight

You're there when the clock gives the warnin'

But there for an hour you will wait

And as you're waiting in the train

You'll hear the guard sing this refrain:

Are ye right there, Michael, are ye right?

Do you think that we'll be home before the night?

Ah you've been so long in startin'

That ye couldn't say for certain

Still ye might now, Michael

(So ye might!)

The West Clare Railway Company’s bad tempered response was to counter-sue French for libel - which gifted him the priceless PR opportunity to turn up an hour late to the hearing in the local Clare town Ennis - and tell the court that he was late because he had travelled there by the West Clare Railway2 - boom! - whereupon the case was dismissed by the judge Baron Palles to peals of laughter. Ouch….

Although the real reason for French’s delay on the West Clare Railway was mechanical - the engine had broken down because weeds had got into the boiler - the song suggests that the West Clare’s reputation for chronic unreliability was the fault of its lacksadasical Irish railway workers - in sharp contrast to the strict time keeping in the rest of the world (there was, by the way, absolutely no evidence that the staff at the West Clare were to blame for its problems; it was part owned by William Martin Murphy - a man later responsible for Ireland’s biggest ever industrial dispute in 1913, the Great Dublin Lock-Out, so it might have been down to underinvestment or understaffing). 3

Time Lord…..?4

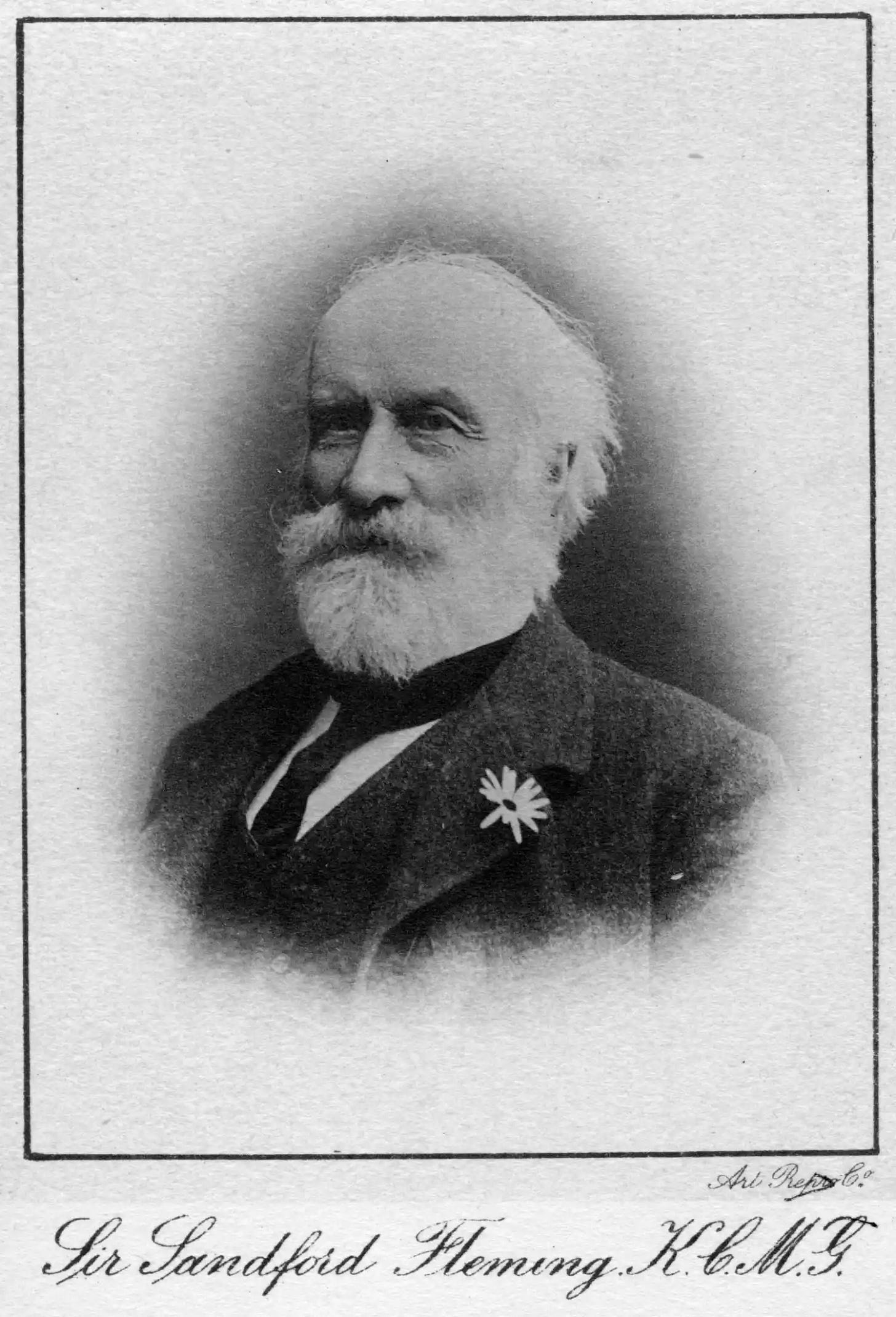

This slur on Irish railway staff timekeeping in both the song and ‘The Quiet Man’ is ironic because it was in Ireland that the whole basis for the standarisation of railway (and thereafter all) world time keeping was conceived. This happened when in July 1867 the Scots-Canadian railway engineer Sandford Fleming turned up to the small railway station of Bundoran after a pleasant day on the beach - only to find that the 5.35 pm train he planned to catch back to the city of LondonDerry and hence to his ferry was not coming - that there was in fact no 5.35 pm train at all that day.

Either Fleming had misread his timetable or it was a misprint - because the only train from Bundoran that day was the long departed 5.35 am and thus he was stranded in rural Donegal with no way of making his ferry back to Scotland. But Fleming spent a very productive eighteen hours in the railway waiting room in Bundoran - he dreamed up the idea of the twenty four hour clock (thus eliminating the am and pm problem), and clearly on a roll - also thought up the concept of a Prime Time Meridian and 15 standard time zones offset from it spanning the globe (although his suggestion of calling this scheme ‘Cosmic Time’ was sadly dropped in favour of Greenwich Mean Time - I’d much rather have lived in the former). He laid out these ideas in his 1879 memoir ‘Terrestrial Time’ and following his return to Canada he became was a key promoter and participant in the 1884 Washington D.C. conference which enshrined these ideas in international law.

This established Greenwich in London as the Prime Meridian from which all global time is measured (which it remains to this day). There was some opposition - the French in particular saw this as a huge expansion of the cultural power of the British Empire, and they held out for Paris being the Prime Meridian until 1911 (this wasn’t just idle talk, in 1894 the French anarchist Martial Bordin attempted to blow up Greenwich Observatory in protest against the global imposition of GMT - dying of his injuries in the attempt - a tragic end to what might have been the punchline to a joke about ‘blowing up time’).

In 1972 the time set by the Greenwich Prime Meridian and its offsets was renamed Universal Standard Time and it remains the mechanism by which the lives of billions of people across the world regulate their lives5. Thus from the factory horns of the early nineteenth century - to the stop watches used on the Somme in 1916 to go over the top - to the strokes of Big Ben at the Millenium Dome in Greenwich; all of these ultimately derived fro m the ideas of Stanford Fleming in a damp Irish train station waiting room - a man who must rank as one of the most influential, yet unknown people in world history.

The Angelus Bell o’er the Liffey swells…6

Although it had originated there, this influence was not immediately felt in Ireland itself as until September 1916 local time in Ireland (known as Dublin Mean Time) was set by the solar time in Dunsink Observatory in Dublin - and this was 25 minutes and 31 seconds behind GMT. However this changed abruptly in September 1916 when - without either public debate or any prior consultation with any Irish parliamentary representatives (who only found out about it a few hours beforehand) a parliamentary bill changing the time in Ireland to be the same as the UK mainland was rushed (railroaded?) through Parliament and passed despite any evidence that anyone in Ireland wanted it.

This generated the suspicion that the real reason for the haste was not the official explanation (supposed business demand) but because during the 1916 Easter Rising earlier that year the time difference between London and Dublin had inconvenienced communications between the British Armed Forces sent to put it down. One person who certainly thought so was the Irish aristocrat and firebrand Countess Markievicz - who had herself narrowly escaped execution for her part in that rebellion and was currently ‘serving time’ in Holloway prison in England as a result. She complained from there about the bill, saying that Irish time itself had been bludgeoned into submission and forced to submit to its English counterpart. Whether or not she was right, it did add further weight to the popular perception in Ireland that when it suited Westminster Irish voices were ignored and it may have contributed in a small part to the growing public pivot away from the Irish Home Rule party and towards the more radical Sinn Fein who advocated the creation of a completely independent republic. In 1918 Sinn Fein won a landslide electoral victory in 1918 - obliterating the Home Rule movement and Markievicz herself was the first ever female Member of Parliament (although she was still in jail and never took her seat in the House of Commons).

(If you’d like to read a bit more about this here:

https://michaelcommane.blogspot.com/2014/10/calling-time.html.)

Closin’ walls and ticking clocks….7

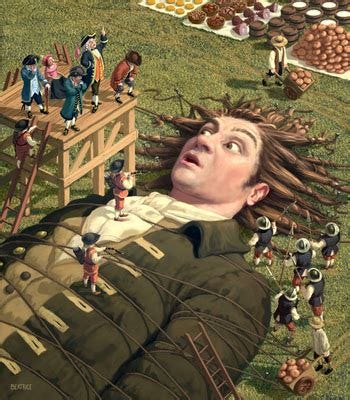

The tiny Lilliputians surmise that Gulliver's watch may be his god, because it is that which, he admits, he seldom does anything without consulting.”

Tensions between Irish and England timekeeping had deep roots - as far back as the early eighteenth century Jonathan Swift, the famous author and Dean of St Patrick’s Catheral in Dublin, had portrayed Enlightenment luminaries like Sir William Petty and Sir Isacc Newton in his 1726 comic novel ‘Gulliver Travels’ as slaves to the newly fashionable pocket watch - constantly checking it like the smartphone of its day.

The pocket watch was just the latest refinement of the mechanical clock, which had been invented by monks in order to regulate time for prayer. As one of my correspondents kindly supplied me with this quote I will use it as it seems particularly apposite:

The paradox, the surprise and the wonder are that the clock was invented by men [Benedictine monks] who wanted to devote themselves more rigorously to God; it ended as the technology of greatest use to men who wished to devote themselves to the accumulation of money [businessmen]. In the eternal struggle between God and Mammon, the clock quite unpredictably favored the latter.” (Postman, Technopoly, 1992, pp. 14-15)

This shifting of the regulation of daily activities away from the natural solar phenomenon to a piece of man made mechanical technology; the clock and then the pocket watch, was a sesmic shift in the abstraction of time which only accelerated in the centuries that followed. In the nineteenth century clocks and watches facilitated the rise of the factories with bells and horns summoning workers across smoky industrial cities across the UK. The invention of the railways with their constellation of timetables, whistles and the regular assembly of individuals unconnected with each other for the sole purpose of travelling had the effect of the creation of a new kind of global time culture (much of the comic value of AYRTM came from its subversion of these expectations).

Nineteenth century Britain and Ireland were Christian cultures and this meant that factory owners had to allow their workers to take Sundays off for church services. But this only break in the working week of the urban working classes gave rise to the phenomenon of ‘Saint Monday’ where hungover workers turned up either late or not at all. In partial discouragement of this, and to give hard pressed workers a wider window for relaxation, in Manchester in 1843 a petition was launched to make Saturdays a half holiday - thus allowing the city to claim the invention of the ‘weekend’ (and I cannot resist shoehorning in here my favorite 2010 scene in the ITV British period drama ‘Downton Abbey’ when Maggie Smith’s Countess of Grantham enquires imperiously ‘What is a weekend?’).

Former railway entrepeneurs like the Scottish writer Samuel Smile’s 1845 ‘Self Help’ book transposed this new matrix of time management from factories and railways onto other areas of life - mantras like ‘time is money’ and ‘time wasting ’ became something that every Victorian school child was warned about. His book was hugely influential and popular in Victorian society and eagerly embraced by capitalists and factory owners who quickly saw in it a powerful new lever to manage the supposedly idle working classes through education and culture.

To enable this, regimes of clocks and bells primed generation after generation of school children to obediently fit their future lives around the disparate requirements of factory horns, drill sergeants, or railway schedules. Further reinforcement came from poems, songs and novels which valorised these values. One example is Rudyard Kipling’s 1895 If:

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds' worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that's in it8

Not even religion escaped these new rigidity around temporal norms, for example the relaxed religious practices of Irish Catholicism gave way in post Famine Ireland to Cardinal Paul Cullen’s insistence on regular Mass attendance in the late nineteenth century. His creation and strict enforcement of a new standard liturgical calendar tightened the iron grip of Rome on the Irish Catholic Church and made few concessions to local customs9 weather conditions or agricultural needs like harvesting or turf cutting - Mass was still held at the same time every Sunday.

A further tightening of the net of time around the lives of the urban working classes came from the Irish-American industrialist Henry Ford who leveraged ideas about time borrowed from men like the American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor to improve productivity in his factories. Like Gulliver tied down by a thousand ropes, workers in early twentieth century Ford factories found themselves accounting for every minute of their working day. These ideas then percolated throughout society in the years that followed until they became an integral part of the silent drumbeat of modern life and an unquestioned secular myth.

Mad Dogs and Englishmen…10

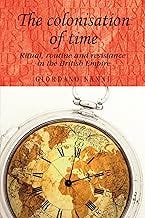

These ideas incubated in the railways and factories of the British Isles, fanned out across the globe carried by the missionaries, merchants and armies of the British Empire. A 2012 book by Giurando Nanni called ‘The Colonisation of Time: Ritual, routine and resistance in the British Empire’ describes this in depth; he relates how indigenous societies like the Australian bushmen - who had previously regulated their lives by natural phenomena like the cycles of the natural world - and who had their own religious ontology of the ‘Dreamtime’ - found themselves instead under an alien regime of bells and clocks which bifurcated their lives into ‘work’ and ‘leisure’ in ways that often made little sense to them (the colonisers were as harsh on themselves as on the natives often maintaining daily schedules that owed more to far distant English weather conditions than to common sense; as the Noel Coward song thrills: ‘Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun’).

But this was not the only disconnection from physical reality which Nanni points out; a particularly jarring example was when the four seasons of the Northern Hemisphere were imposed on places like Australia and New Zealand where they had no anchoring in the natural cycles and were wildly inappropriate to local conditions ‘winter’ occurring in the hottest period of the year. Australian bushmen who had migratory hunting and agricultural patterns linked to natural cycles were forced out of these into regimented sedentary lifestyles (and their land stolen) often at gunpoint - and their children forcibly educated into the new punitive time culture policed by bells and watches the better to fit them as obedient workers on the sheep farms or servants in the new white owned Australia.

This often met resistance, as Nanni relates in Australia where the tendency of the natives to go ‘walkabout’ or to find other ways of subtly undermining the dominant time culture of the colonisers fuelled accusations of supposed native ‘laziness’ and was used as evidence to justify the egregious theft of land under the pretext that it was ‘terra nullis’ - that the natives made no use of it, and merely sat around all day doing nothing.

This had a catastrophic effect on the indigneous Australian populations whose numbers plummeted after colonisation and who are still today suffering its long term effects. White Australia has been slow to recognise to acknowledge these harms but attitudes are gradually shifting - one example of this was the powerful 1987 protest song ‘Beds are Burnings’ by the band Midnight Oil which includes the lyrics about the theft of indigenous land:

The time has come

A fact's a fact

It belongs to them

Let's give it back 11

As well as accusations of laziness, another more subtle weapon flexed against recalcritant natives across the Empire was mockery - AYRTM is an Irish example of the genre, in which the Irish railway staff are painted as charmingly unreliable and lazy (Frantz Fanon in his seminal book ‘The Wretched of the Earth’ about the psychic effects of colonisation points out that supposed ‘laziness’ of the oppressed may in fact be the only form of resistance left when all other forms have been rendered impossible).

The colonisation of Irish time was no less thorough or ruthless than elsewhere in the British Empire or in the UK itself; the division of the island after independence meant that - despite periodic discussions and suggestions otherwise - the whole island still remained on the same time zone as the UK mainland (although I remember flying into Belfast in the mid nineties and the English pilot saying ‘We are arriving in Belfast - put your watch back by 300 years….)

Life in the Fast Lane….12

But this imposition on Ireland of an alien time culture did not always go unnoticed or unchallenged. In a pivotal scene in the 1996 film ‘Michael Collins’ the actor playing the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Lord FitzAlan (respendent in an ostriched trimmed hat) brandishes a pocket watch at Liam Neeson’s Collins dressed in a general’s uniform arriving for the handover of power and snaps at him ‘You are seven minutes late, Mr Collins‘ to which Neeson retorts “We’ve been waiting 700 years; you can have the seven minutes.”

But this is not what happened at the handover on that grey afternoon on the 16th of January 1922 - where there were no uniforms or military parades, instead Collins and his colleagues - revolutionaries dressed in business suits arrived at Dublin Castle jumping out of taxis to a brief 45 minute meeting in a boardroom. Afterwards, without any pretence of small talk or bonhomie with his former enemies, and to avoid waiting press - Collins dashed out of a backdoor (where happily for me he was snapped by an on-the-ball photographer). I find this brief glimpse of Collins - a man caught blurrily mid stride in a hurry - very poignant since he seems to have lived his entire short life at top speed - this extended even to his personal life - ‘In great haste’: the collected letters between Collins and his fianceé Kitty Kiernan published in 1996 got its title from Collin’s sign off on most of them.

But ‘Michael Collins’ doesn’t get everything about the handover wrong, he was indeed late - although Neeson’s retort to the Lord Lieutenant Lord FitzAlan-Howard never happened 13 - it can’t have done - because Collins wasn’t seven minutes late. Instead the real story of the handover on the 16th of January 1922 between the British Crown’s most senior Irish representatives and their revolutionary replacements - which was supposed to happen at exactly 12 noon - was that, on the day itself, Collins left the Crown’s most senior civil servants cooling their heels in Dublin Castle for a full hour and forty minutes - turning up at 1.40 pm (the Lord Lieutenant himself arriving at the Castle a few minutes earlier only summoned when they were certain Collins was on his way). Collins’ biographer Tim Pat Coogan recorded that the Under Secretary James McMahon (perhaps with a touch of exasperation) remarked to Collins on his eventual arrival ‘We’re glad to see you, Mr Collins’ to which he allegedly replied in his West Cork accent ‘Ye are like hell, boy!’

Although the official explanation was that Collins’ lateness was unintentional and due to ‘travelling delays’ - but to me this seems unlikely. In 1920 for instance he had made the grim point of scheduling a mass assassination of British police informants by his notorious ‘Murder Squad’ at exactly 9am on November 21st, 1920 because:

“the British, have got to learn that Irishmen can turn up on time.”14

Perhaps the murdeous determination he showed then hinted at a smouldering resentment against the widely disseminated perception in the British press that the Irish were unfit for self governance; that the new Irish Free State would be run like the West Clare Railway in AYRTM by charming but ineffectual amateurs and after its inevitable slide into poverty and decline it would have to invite back their firm, but kindly British masters. 15

But Collins in my opinion saw through this fiction - knowing that behind the mask of benevolence lay the real aims of the British (and indeed every other Empire in history) which was the exploitation of the land of Ireland and its population. He said as much in the debates supporting the acceptance of the Anglo Irish Treaty in 1922 - that the story of occupation was:

…a story of slow, steady, economic encroach by England. It has been a struggle on our part to prevent that, a struggle against exploitation, a struggle against the cancer that was eating up our lives, and it was only after discovering that, that it was economic penetration. that we discovered that political freedom was necessary in order that that should be stopped.

A key part of that slow economic encroachment in my view was the subtle hijacking over the centuries of occupation of the ability of Irish people to order their lives as they chose through the gradual ratching up of an alien and punitive time culture (which also happened at the same time to the working classes in the UK). This happened so slowly and quietly that few in Ireland noticed it (much as the best fruits of the land itself disappeared across the Irish Sea for so many centuries without much comment).

The British Empire has long gone from Irish shores; but it is not difficult today to see its modern day parallels in the internet corporate giants of Silicon Valley who hook today’s children with smartphones and social media and relentlessly monetise these addictions regardless of the social and emotional consequences (and the smartphones themselves are made from the mineral riches of places like the Democratic Republic of Congo loaded daily on ships bound for the ports of the Global North while the local population starve).

Some of the ways that today’s internet Empires lure their users in is through memes like viral cat or Tik-Tok videos - thus hiding the real societal damage that can lie behind this apparently harmless but potentially addictive content. But there was in my view a possible early forerunner of these insidious present day memes - for example the comic music hall songs like AYRTM which painted the rural Irish as ‘lazy’ and incapable of even running a small country railway properly - thus subtly undermining support for the independence movement (I know, I know see the footnote for caveats).16

But if this was true, what would a sophisticated riposte be to such a pernicious, subtle and enduring falsehood look like? Perhaps one might be in 1922 to deliberately lean into it and wrestle the time of the handover of the island back from the British - to make them wait - to underline the point that it was for an Irishman to decide when it was time for Ireland to be free, that Irish time was for Irish people to live in, to spend as we wished. Collins said during the Anglo Irish Treaty negotiations:

Give us the future..we’ve had enough of your past..give us back our country to live in—to grow in..to love…

Or maybe the Dublin taxi was late….

This was almost certainly a fib on French’s part, since the West Clare, went only, umm, to West Clare and he lived in Cavan. But it was a genius punch line…..

The comic effect was compounded by an earlier case on the same day taken by Mrs Mary Anne Butler against the West Clare Railway for damages after being attacked on a station platform by a malevolent donkey - what a gift that must have been to the journalists waiting for the French case!

This meant that Greenwich became, and remains the ‘Omphalos’ of the world, the place from which all the time across the globe is measured, or offset.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46473/if---

(such as the visiting of Holy Wells on particular saints’ days - but this persisted nonetheless in many rural areas until fairly recently).

although it may have been seeded in the press by Collins’ formidable PR machine since the line comes from a story floating around Dublin shortly after the handover, coincidence much?

Hitler also weaponised time in a more sinister way later in the century keeping the unfortunate Czech leader President Hacha waiting until the early hours of the morning in 1939 to push through his demands for complete capitulation.

and this view was not confined to the British press - it was also widespread amongst some of the Irish middle classes, particularly in Dublin, who had benefited most from colonisation - those, as Yeats wrote in his poem September 1913, who ‘fumble in the greasy till ’.

I am not saying that this was Percy French’s intention but he was a deeply enculturated product of his privileged class (Anglo-Irish Protestant) and I believe he hit upon a widespread seam of contempt for the rural Irish which erupted in the laughter of the music halls; no less damaging for being unconscious on both the part of the composer and his audiences, nor for being laced with affection as in ‘The Quiet Man’. The widespread Irish 'jokes’ which were widespread in the UK until fairly recently were also in my view a subtle and damaging way of doing the same thing. You don’t hear them much these days……either we are a lot smarter, or they have stopped being funny.

Thank you for this. The imagined stuff that appears as most material to us - like clock time and money - are the most powerful and pernicious!

I'd forgotten all about that money burning scene in The Quiet Man.

Have you heard of the French anarchist Martial Bourdin who died trying to blow-up GMT in 1894. The story is in John Higgs' Stranger Than We Can Imagine where I think he conceptualizes GMT as an 'omphalos'.

Struck me as relevant:

“The paradox, the surprise and the wonder are that the clock was invented by men [Benedictine monks] who wanted to devote themselves more rigorously to God; it ended as the technology of greatest use to men who wished to devote themselves to the accumulation of money [businessmen]. In the eternal struggle between God and Mammon, the clock quite unpredictably favored the latter.” (Postman, Technopoly, 1992, pp. 14-15)