This is based on my recent experiences after Storm Éowyn. I’ve referred to two songs, the Irish language song An Puc ar Bui (The Mad Goat) and the brilliant anti war song ‘Oliver’s Army’ (with a warning of some discriminatory language) you may want to listen to them first, here: 12

One of the most popular, but odder songs in the Irish language is about a wild billy goat: An Puc ar Bui starts with a man on his way to take part in a meitheal (an Irish co-operative work party) before a feral mountain billy goat chases him before charging off down the mountainside to cause mayhem in the local town. The song is a poem by Dónal Ó Mulláin set to the beautiful music of Seán Ó Riada and it pays homage to the herds of wild goats which roam the mountains of one of Ireland’s most beautiful landscapes, County Kerry.

The eponymous goat of the song is Puck and some years ago I visited the famous Puck Fair in picturesque little Kerry town of Killorgin where every year a wild male adult goat is captured from the nearby mountain, put in a cage, and hoisted in the air over the town for three days in August presiding as the honorable ‘King Puck’ of the Fair whilst horse trading, fairground attractions and merrymaking go on all around him3. (The origins of the fair are uncertain, but it goes back to at least 1603 when there was a charter issued by James I of England).4

Because of family ties I travel between Ireland and England fairly frequently and have just returned from a trip to the West of Ireland; en route I stopped to visit my uncle in Dublin, and we chatted about his childhood growing up in rural Ireland. He mentioned one of the most trying times of this was the Great Blizzard of 19475 where there was snow on the ground between January 1947 and the 10th of May of the same year, how close they came to starvation, and how difficult it must have been for his parents with six small children on a small rural farm without electricity, heated only by turf fires and living on home grown produce. He talked about important it had been for the community to depend on each other to pull through ‘everyone helped each other, you had to’. We talked about the tradition of meitheal (which I have written about here) and how crucial it was to the survival of Irish rural communities.

We’re Not In Kansas anymore….

This was an oddly prescient conversation because just after my arrival in East Galway Storm Éowyn noisily arrived in from the Atlantic with enormous gusts of wind blowing tiles off our roof and littering the local roads with fallen power cables and uprooted trees. There was no electricity, no mobile signal or internet in our rural East Galway farmhouse. Thankfully we had a coal fired stove in one room to keep warm and cook on, but the rest of the house was freezing. We were more fortunate than some of our neighbors living in newly constructed houses with no fireplaces or chimneys who were completely reliant on electricity for heating and the temperatures plunging to near zero. The night horizon was a wall of inky blackness and the sky a glorious twinkling velvet carpet studded with stars (a view I had ample opportunity to admire whilst standing at the bottom of a neighbor’s ladder as he fixed his roof during a gap in the storm).

We only lasted a few days in these conditions; for safety reasons we needed to decamp to relations in the city. Even in these few days it became clear that the old rural tradition of meitheal which seemed to have disappeared under the waves of modernity may actually only have been lying under the surface, waiting for the right conditions to emerge. Several neighbors called in offering lifts to stock up on provisions and in the only local supermarket powered by a generator, crowds of people swapped storm stories and advice and stocked up on supplies. I hitched a ride with a friend to Loughrea, the nearest big town, where the streets were buzzing and all the cafes awash with people using the wi-fi to let the outside world know they were safe (there was a definite Alice-in-Wonderland vibe to the whole experience, only here the White Rabbit had a mobile phone and said ‘bye,bye,bye’). Here everyone had an opinion about when power would be restored, a story of storm damage and how soon things would go back to normal. Meanwhile life in Ireland’s major cities went on largely unaffected.

I know that three days is not long to appreciate how difficult it is to exist without the trappings of modernity, but it is a taste that I will not quickly forget. Our wonderful neighbors (to whom I am very grateful) had to endure a further five days without essential services in freezing temperatures, but the WhatsApp chat they set up was a fascinating glimpse into a community coming together in real time as they tipped each other off about water sources, checked in on each other and discussed the current status of power restoration. As a real time example of a meitheal coming together in difficult circumstances it was truly inspiring to witness.

Today Irish people shop in supermarkets like Aldi and Lidl and have a diet which spans a variety of food groups drawn from all over the globe, so the failure of a particular food today would no longer have catastrophic consequences. But the Irish in recent years have become largely dependent on one energy source, electricity; for their heating, their water supply and of course the internet. But this reliance on electricity means that they are vulnerable to its sudden failure, as we quickly found out after Storm Éowyn. Encouraged by the Irish government to install electric air source heat pumps and without any fireplaces, the newer properties in rural Ireland quickly descended into freezing conditions, leaving only those older properties who still had fireplaces with any form of heat. And those who with electric vehicles were stranded without transport, only those with petrol and diesel powered tractors, cars and trains could find food, warmth and information. (When we did reach the local shops still open, cash was the only means of payment as card machines were inoperable).

Oliver’s Army

Storm Éowyn is a natural disaster, but like the Great Blizzard of 1947, Ireland is no stranger to those, nor to man made disasters like wars or famines and the lines between natural and man made are often blurred. One of the worse disasters in Irish history was Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland in 1649, where over a period of ten years some estimates that up to a fifth of the island’s population may died as a result of war, famine or disease6. Cromwell’s invasion had been partially prompted by the earlier Irish 1641 Ulster rebellion in which many Ulster Protestants had been killed; this kick started a vicious Irish and anti Catholic propaganda campaign like Sir John Temple’s 1646 ‘The Irish Rebellion…With the Barbarous Cruelties and Bloody Massarces which ensued thereupon7’, a highly partisan, incendiary, but deeply influential account (think the Fox News of its day) which made a hugely damaging impression of Ireland on English public for many years to come. Cromwell himself seemed to draw from this to justify the mass slaughter at the Irish towns of Wexford and Drogheda in a classic case of victim blaming as he said after Drogheda:

I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood; and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future.8

Oliver Cromwell only spent nine months in Ireland in 1649, but he still looms large in the Irish psyche, as well as being the eponymous inspiration for Elvis Costello’s 1978 anti war song ‘Oliver’s Army’, an other more recent anecdote was in 1997 where the then Irish taoiseach Bertie Ahern allegedly refused to sit in an room containing a portrait of Oliver Cromwell whilst visiting the British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook in Westminster9. What is certain is that in 2017 the award winning gin sold in the UK by Aldi as ‘Oliver Cromwell London Dry Gin’ was rebranded as ‘Corley Gin’ (me neither?) for sale in Ireland because as Dermott Jewell, chief of the Consumers’ Association of Ireland remarked:

You can put money on it that the marketing men at Aldi didn’t think it was a good idea to sell it under the name Oliver Cromwell in Ireland!10

Perhaps even more than the headline massacres of Wexford and Drogheda (over 2,000 killed in each in systemic slaughters which were considered well outside the norms of contemporary warfare)11 a large part of the continued Irish animus towards Cromwell is the blame attached to him for the decision of the English parliament in 1654 that:

all the ancient estates and farms of the people of Ireland were to belong to the adventurers and the army of England, and that the Parliament had assigned Connaught for the habitation of the Irish nation, whither they must transplant their wives and daughters and children before the First of May following (1654) under penalty of death if found on this side of the Shannon after that day12

This was widely interpreted as the infamous invitation to the Irish ‘to go hell or to Connaught13 (although Cromwell himself probably never uttered those words). 14 This resulted in a massive internal forced migration westward, one of the largest in modern European history, causing enormous suffering and radically altering local demographics, something which can be still seen in the surnames of Galway to this day. (Coincidentally the court which decided which bits of Connaght were to be doled out to these incomers, sat in Loughrea15 where I watched their present day descendants busily wheeling gas heaters out of the town’s hardware store and stacking their car boots with bottled water from its supermarket).

The Crow’s Nest

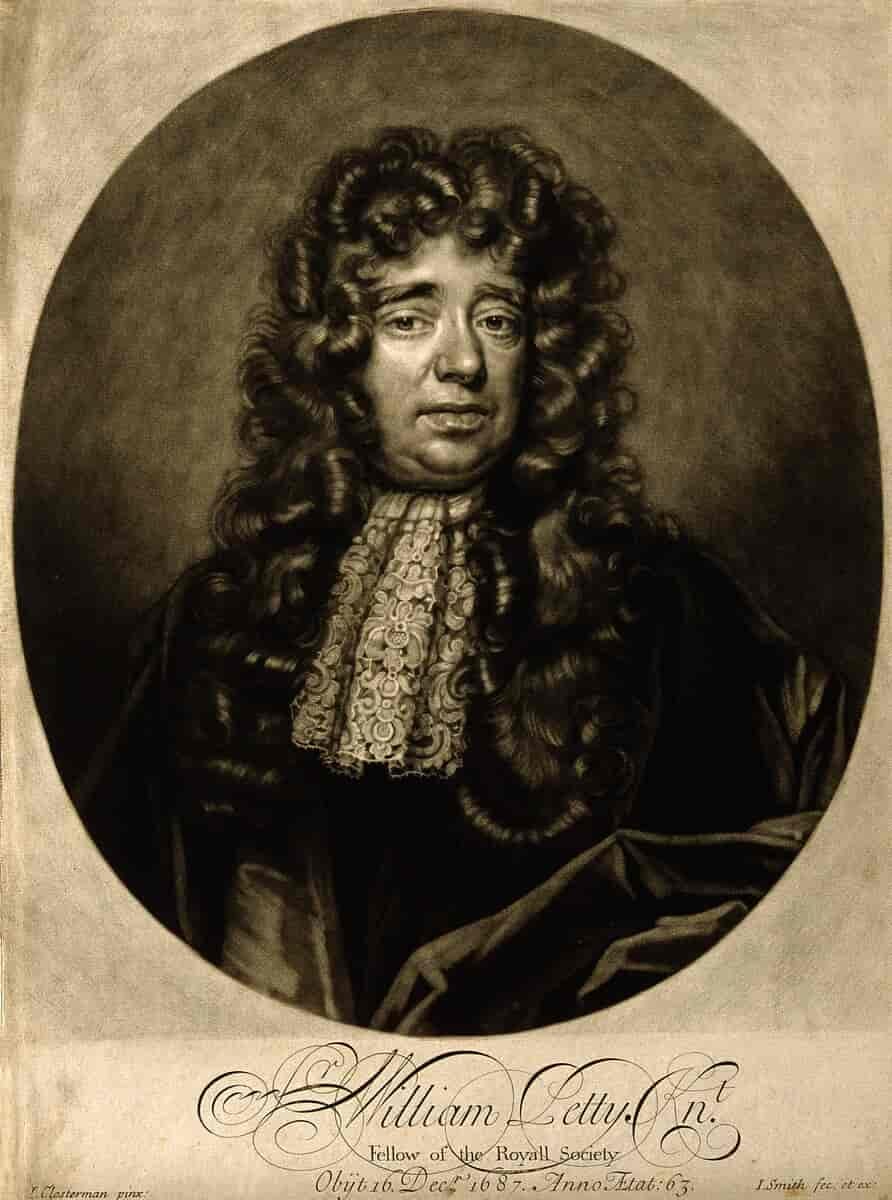

One of the chief beneficiaries of the Irish Cromwellian land transfers was Sir William Petty,16 a Hampshire working class boy made good who managed to scramble up the social ladder thanks to a unique combination of both a Jesuit and an Oxford education, and a truly astounding amount of chutzpah and good luck (a key plank of his personal brand was that he had once managed to resuscitate a woman hung for murder). He was a political shape shifting networker who managed to skip nimbly between the Cromwellian period and the Restoration of Charles the Second, and a scientific polymath: a 17th century mash up of JD Vance, Mark Zuckerberg and Professor Brian Cox (as well as a medical doctor, inventor of double hulled ships and an Oxford Professor of Music).

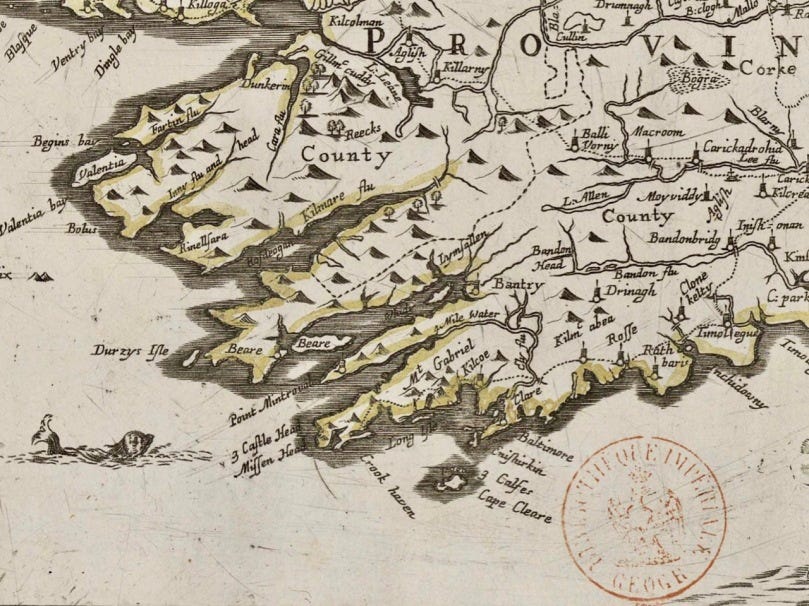

One of the first things Petty did on his arrival in Ireland in 1652 was to take over the Down Survey, one of the first attempts by a state to almost completely map a country -the better to dole it out to the Adventurers’ (private individuals and London corporations who had financed the English state’s Irish campaign in return for the promise of land, a proto public/private consortium) and the ‘army of England’ - the Parliamentary ‘New Model Army’ (the original Oliver’s Army)17. This was the first to require its soldiers to serve outside their local areas and to prohibit political office for its soldiers, where promotion was on merit, and well trained and disciplined; it is thus widely considered the foundation of the modern British Army.18

However the creation of a modern army with professional soldiery had one serious drawback, they needed to be paid regularly something the cash strapped English parliament was unable to do. Their ingenious solution in 1654 was to make the Irish pay for their own conquest by handing over their land. The difficulty with this was that at that point no one knew exactly how much land there actually was in Ireland as it had never been accurately mapped.

On his arrival in Ireland Petty took over a somewhat shambolic previous effort and turned it into a slick operation which became the first successful cadastral19 mapping project of an entire country in world history20. From his Dublin office -nicknamed ‘The Crow’s Nest’- on Crow Street in Temple Bar he employed teams of surveyors, (whom he called his ‘instruments’) to fan out over the landscape measuring it out using surveyor’s chains. These men, mainly demobbed Cromwellian soldiers owed money by the state (thus killing two birds with one stone), were kept deliberately in the dark of the overall purpose of the project, as were the suspicious natives, some of whom nevertheless quickly twigged that the mapping project was a precursor to the subsequent theft of the land and treated the surveyors accordingly.21

Eight of them were surprised….and executed as accessories to a gigantic scheme of ruthless robbery22

From his perch in the Crow’s Nest, Petty build up a data model of entire Irish counties, the better to estimate their potential for exploitation and to consolidate the English state’s hold on Ireland (two and a half centuries later Number 3 Crow Street was where Michael Collins, the Irish revolutionary leader ran his office23, to do precisely the opposite). Petty saw Ireland chiefly through the lens of its economic utility to England; he was accused of wanting to turn Ireland into a giant food factory to supply the English market and keeping the Irish just as laborers24 for this project, whilst wanting to ship the rest to England. Certainly he viewed the administration of Ireland as a type of cold blooded anatomical dissection saying:

I have chosen Ireland as such a Political Animal, who is scarce Twenty years old, where the Intrigue of State is not very complicated.. I have had only a common knife, and a Clout , instead of the many more helps which such a Work requires : However my rude approaches being enough to find where about the Liver and Spleen, and Lungs lie25

Western Ireland in his view was excluded from this as mainly useless barren land, fit only as a vast open air prison camp for the island’s recalcitrant inhabitants, and anyone who objected to the project was either shipped to Barbadoes as a slave26, or shot. Petty completed his task in an impressive 13 months and used the opportunity to scoop up vast areas of the island for himself, he was the largest landowner in County Kerry, and it is said that from the top of Mangerton Mountain in Kerry everything he could see was his. Thus he might also have been one of the first modern examples of what the author Namoi Klein in her 2007 book has called ‘disaster capitalists’27, people who swoop in in the aftermath of disasters to scoop up valuable land or resources, something which has modern parallels after the recent fires in Hawaii and New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.28

Even after Oliver Cromwell’s death and the restoration of Charles the Second, Petty managed to both hold onto his newly acquired Irish property and to inveigle himself into the new King’s good graces, no doubt helped by his coterie of influential London friends. He was a close friend of Thomas Hobbes, John Evelyn, Samuel Pepys, John Locke and many other other Enlightenment luminaries.

His experience of mapping Ireland also contributed to his development of what he called ‘political arithmetic’, what was later developed into modern economics and the field of statistics29. He became both one of the founding members of the Royal Society in London, and it’s Dublin twin, the Philosophical Society (later the Royal Dublin Society). In my view Petty’s fingerprints are all over the modern political landscape in all kinds of interesting ways; he made good on his promise to use Ireland as a test bed for political experiment which he then brought back to advance the imperial project at home30.

Now what will we do for timber? (Créad a dhéanfaimid feasta gan adhmad?)31

The Cromwellian land confiscations which Petty’s survey enabled have a very long slipstream, one which still impacts the Irish landscape today. It completely disrupted the whole island’s food ecosystem and inserted into it instead an Anglo Irish colonial elite who viewed the land chiefly in economic terms. To that end they devastated the ecology of the island, cutting down the majority of the native forests, the 19th Irish politician John Mitchel wrote of Petty that:

For years the ancient vales of Dunkerron and Iveagh rang with the continual fall of giant oaks….there was no source of profit…in which Sir William did not have a hand32

-to this day Ireland remains one of the least forested areas of Europe33. Petty decimated the forests of Kerry both to feed a charcoal industry, and also in what might be one of the first documented examples of ecocide, in order to destroy the hiding places of the Irish ‘woodkernes’ rebels (something the Americans did in Vietnam in the twentieth century with their use of Agent Orange to destroy the jungle hideouts of the VietCong). The destruction of Irish woodlands was bewailed by an anonymous composer in one of the first modern eco protest songs, the beautiful ‘The Lament for Kilcash’34.

The boys from the Shannon, Bann and Boyne

In accordance with Petty’s vision, he and his fellow Anglo Irish land owners disrupted the native food culture turning the most fertile land on the island to large scale dairy or beef farming, or to cash crops of wheat, barley and dairy products for the English market. The native Irish response to this was to increasingly to turn to one crop, the energy and vitamin rich potato, a South American import which had been introduced to the island in the late seventeenth century35. This highly calorific ‘super food’ became the principal means of nutrition for most of the native population which consequently boomed during the nineteenth century to a peak of nine million people in 184536.37

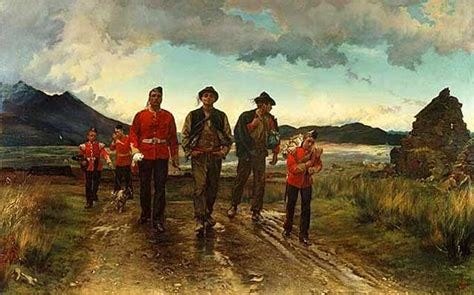

This was so successful that Ireland became the preferred recruitment ground for the British Army as the tallest and healthiest recruits were found there compared to their often sunlight deprived and undernourished working class English counterparts and it is estimated nearly a third of the British Army in the nineteenth century was Irish38. Oliver’s Army in the nineteenth century was drawn as much from the Shannon, Blackwater and Boyne as from the Mersey, Thames and Tyne of the song.

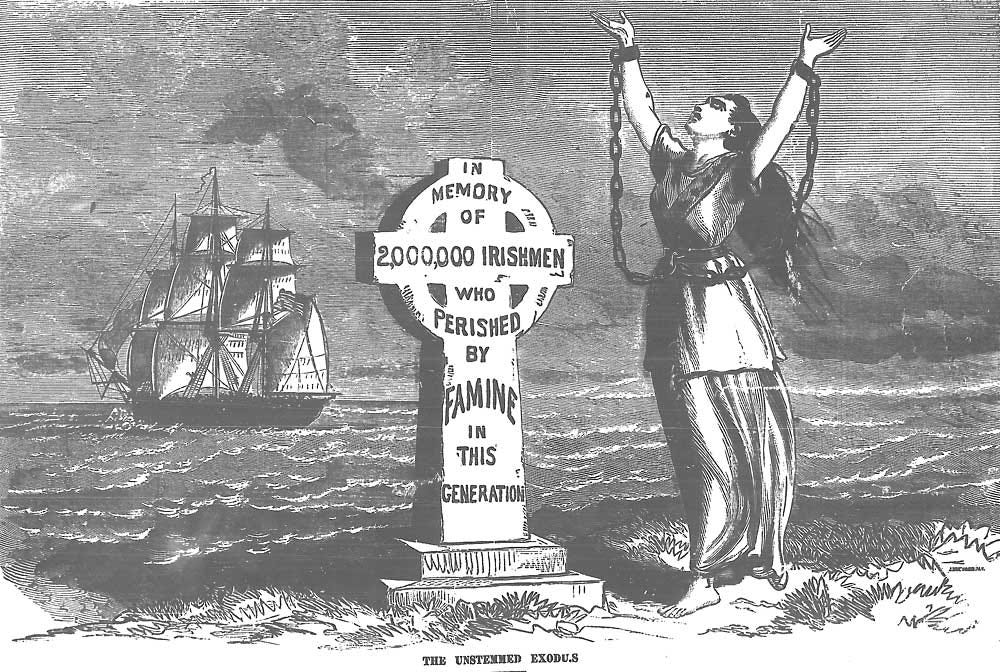

However the heavy reliance on the potato had one huge drawback, it was susceptible to disease and sudden catastrophic crop failures. This happened again and again during the nineteenth century culminating in the Great Famine of 1847-151 during which it is estimated a million people died, and another million emigrated, a population collapse which Ireland has still never fully recovered as it still has less people today than it did in 1847.39 (Amongst those Famine emigrations, some of the more controversial were from the Lansdowne Estate in Kerry owned by Petty’s descendant, the English based Marquess of Lansdowne whose tenants on his picturesque but barren Kerry estates were notoriously poverty stricken and uniquely vulnerable to the frequent failures of the potato harvest40.)

So Cold In Ireland41

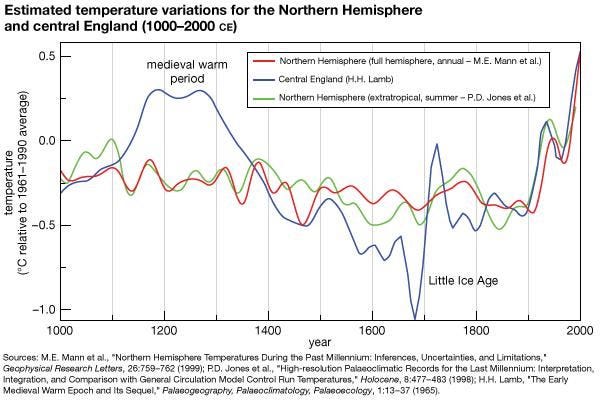

Today, we discuss storms such as Éowyn as a likely result of of what most scientists agree is human induced climate change resulting from the burning of fossil fuels since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century42. However climate change itself is not a new phenomenon. A recent book by Geoffrey Parker called ‘Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century’ examines recent research which indicates that during the so called ‘Little Ice Age’ from 1500-1800 the average temperature may have dipped nearly two degrees below average. There were also extreme weather events such as the complete freezing of the Bosophorus strait between Europe and Asia as well as the Frost Fairs of the Thames when the river froze over completely.

In a pre industrial wholly agricultural society these weather fluctuations caused many crop failures, trade disruptions and often profound human and animal suffering. Parker posits that these climatic conditions may have lain at the root of the unusually high levels of war and societal disruptions during the peak of this period between 1600-1800 known as ‘The Great Crisis’ a time which included the Europe wide conflagration known as the Thirty Years’ War, the fall of the Ming Dynasty in China and into which the 1640s and 50s conflicts of the English Civil War and Irish Cromwellian fell squarely in the middle.

Oh,Clinical, oh intellectual, oh cynical…43

Towards the end of the ‘Great Crisis’ came the Enlightenment in the 1680s, an intellectual movement to which Petty and his London friends belonged; that period in which much of the beliefs which undergird modernity were formed, the operating system if you like, of our modern life44. These include beliefs such as the development of the modern scientific method, the idea that citizens cede the power of retribution and violence to the state in exchange for protection and individual liberty found in the work of John Locke) as well as hugely influential books like Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (from where the description of primitive life as ‘poor, nasty, brutish and short’ come)45 It also contains the seeds of the present day rule of law and many other of modern political theory and scientific methods. But these ideas were written by men who were deeply involved in the wars and crises of their age, and in at least some cases, probably also deeply tramatised by.

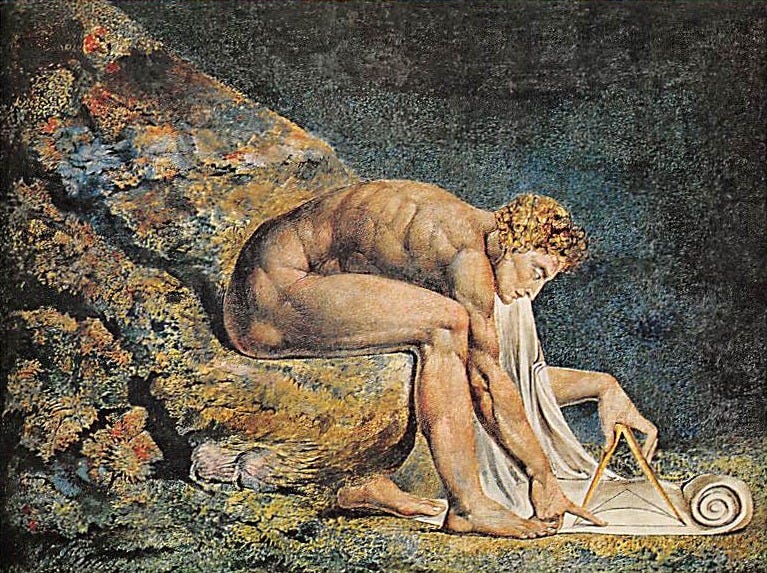

This was certainly the case for Thomas Hobbes who had lived through the English Civil War, and it may also have influenced the later ideas of Descartes who had been a soldier in the Thirty Years’ War46. The link between Enlightenment ideas and the political and society conditions in which they were birthed is not conclusive, but it certainly seems likely in my view that individuals seeking order and stability in a chaotic world should construct mental models of reality which valorised rationality, order and logic. There were a few in later years, like the poet William Blake who pushed back against this form of thinking as ‘Newton’s sleep’ 47, but in the main this mental scaffolding formed the basis for the new industrial age in the nineteenth century which followed with its data driven models of the world. This relied heavily on technology and industry as promoters of human flourishing and it is the one in which we largely still live in my view.

Riders on the Storm48

Today it seems to me that we may be about to face another era of climatic change, and thus possibly a new age of wars over energy and resources. Perhaps it is also possible now that the Enlightenment ideas which have reigned virtually unchallenged for the last three centuries might now also be challenged. One indication of this are the recent populist emotion driven politics of today, which may indicate a dawning realisation that emotional states like anger and fear are part of the human condition which may have been too long ignored by political elites.

And if this is the case, if the Enlightenment ideas are indeed seeping away, what new mental operating systems might arise to take their place today? And who will benefit from them? Are today’s Crow’s Nests and modern day William Pettys to be found in Silicon Valley from where their ‘data driven’ models of artificial intelligence will steam roll over the actual physical landscapes, cultures and the people who inhabit them? Should we let ‘disaster capitalism’ free rein in the aftermath of war or climate disasters? (there are some depressing portents for this recently).

Above all what are the alternatives? Perhaps some of them at least might be found in the meitheal traditions of rural Ireland. Can we be like rural Ireland in the Great Blizzard of 1947 where a pre industrial agricultural society managed an extreme weather event by leaning on the bonds of community? Storm Éowyn showed me that during extreme weather events these bonds can spring up, but on other visits I have also heard that they just as easily atrophy, as local community organisations are withering because most people are ‘too busy’ working to participate.

And if you are still with me on this trip down a 17th century rabbit hole (well done you!) this is where I tell you what I think goats, 17th century Ireland and climate change have to do with each other. According to local legend, the reason King Puck is honored at the August Fair in Killorgin is in gratitude for saving it when a Cromwellian army on its way across the mountain to ravage the town disturbed a herd of feral goats. The herd’s Puck Goat ran down the mountainside running amok but in the process alerting the townspeople to the oncoming danger from the army. Maybe Storm Éowyn and others like New Orleans’ Storm Katrina are today’s Puck Goats, causing chaos, but as in Elvis Costello’s 1978 song reminding us that once again:49:

Oliver’s Army is on their way, Oliver’s army is here to stay

Or maybe not…you decide.

https://songsinirish.com/?song=an-poc-ar-buile

https://www.theirishroadtrip.com/puck-fair-killorglin/

The goat is well cared for and carefully supervised by a vet and locals insist that it is not detrimental to the animal’s welfare (although some animal rights activists remain unconvinced).

https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/remembering-the-great-irish-blizzard-of-february-1947/34482677.html

https://downsurvey.tchpc.tcd.ie/

https://archive.org/details/nd6733699/page/n23/mode/2up

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cromwell_letter_to_William_Lenthall

https://www.almosthistorypodcast.com/take-down-that-murdering-bastard/

https://extra.ie/2017/07/31/business/oliver-cromwell-gin-aldi

‘God’s executioner’ by Dr Micheál Ó Siochrú.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1915/rcoi/chap01.htm

Ironically the man who is reputed to have executed Charles I, Colonel Peter Stubbers,is supposed to have retired to Galway City where there’s a pub called The King’s Head named apparently in his honor https://thekingshead.ie/

For a discussion as to whether Cromwellian policy in Ireland was genocidal or not see the book ‘God’s executioner’ by Dr Micheál Ó Siochrú. There are some obvious modern parallels with the current tragic situation in Israel/Gaza.

https://legalblog.ie/cromwellian-reconquest/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/531027

the foundation of the oldest regiment continually serving in the British Army the Coldstream Guards is from this

https://www.britannica.com/topic/British-Army

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cadastre

https://www.cambridge.org/core/blog/2024/01/22/william-pettys-survey-of-ireland-and-the-role-of-natural-history-in-the-development-of-statistics/

https://www.libraryireland.com/biography/SirWilliamPetty.php

In my view, the Down Survey with its use of oblivious workers has striking parallels to the work of artificial intelligence bots scraping the internet for training data in order to create Large Language Models like ChatGPT and the mutinous natives present day opposition by creatives such as Paul McCartney). Less obviously I was also reminded of Petty’s project recently when reading of Irish born Fintan Slye, chief executive of the UK’s National Energy System Operator who talking about his wish to create a ‘digital twin’ of the physical UK transmission network, the better to manipulate and make predictions about future energy usage. Fintan might like to consider that the recent storm bent a giant wind turbine in Galway in two, something no digital twin could ever predicate.

http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/rebellion/intelligence-war/

Eamon De Valera several centuries later made the same accusation that British Imperial project’s ambition for Ireland was only as ‘her kitchen garden’

https://archive.org/details/nd7904454/page/n15/mode/2up?q=body

This was also a period in which many Irish who were shipped off into slavery in Barbadoes (the origins of the present day ‘Red Legs’ communities, the Red Legs being a reference to the sunburnt legs of the slaves under their traditional kilts).

https://tsd.naomiklein.org/shock-doctrine/the-book.html

https://scalawagmagazine.org/2023/09/maui-wildfires-response/

https://samizdathealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Petty-in-ireland-fox-pub1.pdf

ibid

https://www.libraryireland.com/biography/SirWilliamPetty.php

https://www.mapsofworld.com/europe/thematic/countries-by-forest-area.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecocide

https://www.pdx.edu/challenge-program/sites/challengeprogram.web.wdt.pdx.edu/files/2021-06/Lewis_Ruby_Paper_and_Abstract.pdf

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1015403/total-population-republic-ireland-1821-2011/

https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/ireland

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/timeline-ireland-and-british-army

https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Famine-Irish-history

‘The Lansdowne Estate in Kerry Under the Agency of William Steuart Trench, 1849-72’, GS Lyons, 2001.

https://external-content.duckduckgo.com/iu/?u=https%3A%2F%2Ftse3.mm.bing.net%2Fth%3Fid%3DOVP.hyWSMWNxgBYjraIqXkFVOQHgFo%26pid%3DApi&f=1&ipt=7a8d2856b2eb4723e77d43bc477a87057f125f876b41f31f1ae1cdc6493d47cc&ipo=videos

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/blog/2025/a-look-back-on-storm-eowyn

https://www.britannica.com/event/Enlightenment-European-history

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Leviathan-by-Hobbes

https://academic.oup.com/book/41694/chapter-abstract/353936638?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false

‘William Blake, the Single Vision and Newton’s Sleep: A History of Science, Poetry and Progress’, 2023, Keith Davies

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=Oliver%27s+Army&atb=v273-1&t=chromentp&iax=videos&ia=videos&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3D0SCf5F6pKvw

Costello has said that the song is a critique of British imperalism using working class boys to prop up its empire and the whole ‘Our Boys’ mythology behind it. He has asked for the song not to be played in public due to controversy over the line about white n………, a racial slur used about Catholics in Northern Ireland.